CONTINUING CONFUSION OVER THE PUDU BREAKOUT EIGHTY YEARS ON

Investigating Reg Newton’s story leads naturally to examination of that formative period in his captivity between February 14th and October 1st 1942 when he was imprisoned in Kuala Lumpur’s Pudu Gaol. Towards the end of that eight-month stint, on the night of 13th/14th August, there was an escape attempt involving eight prisoners, seven of whom were executed on September 16th 1942. Despite there being six eye-witness accounts and at least six serious attempts by historians to unravel details including the precise timeline of these events, the deeper I dig, the more complex the problem becomes. So, lest this article bore the breeches off readers, it will be divided into two sections: the first will cover what can be established with reasonable certainty about the breakout; the second is not recommended for the faint-hearted and will be of interest probably only to two or three other people on this planet and they will be individuals with a stake in the story and with sufficient commitment to follow the paper trail. That being said, I will press on regardless because I have found the reading, the investigation and the thinking absorbing. Readers of course have the option to bail out at any time (and I will include plenty of ‘Back to the Top’ hyperlinks for that express purpose). My aim in the second section is to show the reasoning behind the timeline given in the first—which varies in significant ways from every account that has gone before. This may sound both presumptuous and improbable but the remarkable thing is that of those six eye-witness accounts and six postwar histories, none agree on all the details, each has significant errors of fact and if any single account were accepted, it raises irreconcilable questions. Fact.

As a result, what is offered here is a best-fit of the evidence available. I cannot swear on a stack of Bibles that this is the definitive account or that it will not subsequently change. In fact, I would welcome that change because that would mean we were one step closer to a degree of certainty and a final resolution. Accordingly, should any reader feel I have overlooked important detail or wish to find fault with my thinking or conclusions, then I am more than happy to hear from you. There is a contact page which should be accessible through the link I have added or can be accessed at the top of this page.

The Pudu breakout was an important episode in the Reg Newton story. It was by no means the first or even the last attempt to escape Japanese captivity but it involved eight brave men who put everything on the line to get back into the fight against the Japanese, knowing the dreadful risks and ultimately making the supreme sacrifice to show others the futility of similar attempts. That knowledge shaped the attitudes of those POWs who remained. For instance, when they were on work parties, being transported or working in remote jungle locations, getting away was deceptively easy; staying away and staying alive were different matters and, while neither was entirely impossible they were so near to it as to be of no account.

The tragic fate of the escapees showed the folly of the escape option. While things were bad under Japanese suzerainty and while over a third of all POWs were to die in captivity, two-thirds lived and that was a much higher percentage than would have survived by escaping. During the whole of the Pacific War, there were only a handful of successful escapes and a number of these occurred very near the end—as at Sandakan—when the risk for local people sheltering Allied soldiers was considerably lower than it had been at any time in the previous three years. The terrible price paid by POWs for commitment to a sit-and-wait strategy was also significantly lower than would have been the case had they risen up against their captors, as was considered at times on the Railway and in hell-ships where POWs out-numbered guards many times over. Of course, the Japanese attempted this at Cowra, NSW, in August 1944 but their intention in that breakout was not escape. How could it be in the rural heartland of an island continent where young men of Asian appearance speaking little of the language stood out like sore thumbs? But Caucasians in Japan’s Greater East Asian Co-Prosperity Sphere stood out just as prominently and the Japanese exacted terrible retribution on whole villages suspected of harbouring or assisting escaped Allied prisoners.

That knowledge gave prisoners the focus they needed to do what Emperor Hirohito later said his people should do and that is endure the unendurable. It encouraged the POWs to listen to their officers and to remain as a unified body of men after a phase when faith in the system and higher commanders had been seriously undermined; it helped stem a groundswell of resistance to discipline and control which flowed from capture and capitulation and it made men realise their best chance of salvation would come from within—not from within themselves as individuals because no man could survive alone, but from within the group as a result of the co-dependence and cooperation it fostered. As such, the Pudu escape was a watershed event.

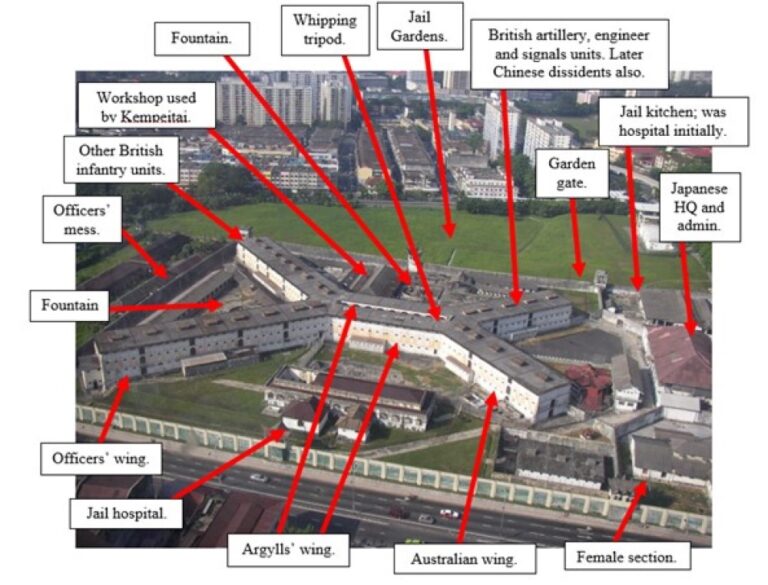

Aerial View of Pudu Prison, Kuala Lumpur.

SOURCES: Joseph Gan, Wikipedia; Map of Pudu drawn by Charles Edwards from

Frank Larkin POW Website; & ‘The Grim Glory of the 2/19th Battalion’ (2006) p.395.

In the discussion that follows there will be questions raised about the reliability of different versions told by eye-witnesses but it needs to be understood at the outset that that is not intended to be disrespectful nor even critical. Such scrutiny is the inevitable consequence of seeking to unravel a story in which so many details conflict and where there are internal inconsistencies in almost all the versions told. This is no one’s fault; nor is it the result of any lack of goodwill on the part of any POW. It comes with the package we sign up for when we join the human race. For all our strengths and attributes, the memories of homo sapiens are not entirely reliable. Furthermore, in Pudu the escape plan was hatched in secret; only bits of the story were dripped to certain people; the escapees were prevented from communicating with other inmates after they were returned and the Pudu rumour mill would have been grinding in over-drive filling gaps in knowledge wherever they existed. One need only read the diaries of former POWs including Pte Alex Drummond to see how unreliable a source of information that could be. So sorting the wheat from the chaff all these years later is no simple task.

When concluding his 1966 account of the breakout, L/Sgt Ken Harrison wrote: “while the men of Pudu live, their memory will live also”. We are coming up to the 80th anniversary of this escape and its ensuing executions. It will not now be long until the last of that great-hearted generation which included the former prisoners will leave us. Those whose liberty and lifestyles were secured by their sacrifice will be forever in their debt and a little accuracy is the least we can offer in return. It is in that spirit that this esoteric discussion will proceed.

THE ESCAPE TIMELINE AND ITS PERSONNEL

The first-person accounts of the Pudu escape come from Capt. Reg Newton, Gnr Russell Braddon, 2/15th Fld Reg., L/Sgt Ken Harrison, 2/4th Anti-Tank Reg., Pte Alex Drummond, 2/29th Bn, Lt Pat Garden SSVF and 101 STS, and Pte Charles Edwards, 2/19th Bn. The historians who have written of the escape are Dr Hank Nelson, Peter Brune, Lynette Ramsay Silver, Dr Katie Lisa Meale, Steven Snelling and Audrey Holmes McCormick.

So, to explain, there has been confusion over the identities of the escapees but I am satisfied that the eight who broke out on the night of 13th/14th August consisted of two distinct and separate parties, which is as reported in the 2/19th’s unit history and confirmed by the incomplete copy of a letter written by Capt. Mick MacDonald to his wife before his recapture. However, this view is in contrast to the first-person accounts of Russell Braddon, Ken Harrison and, to some extent, Alex Drummond. The members of the two parties were:

Vanrenen’s ‘official’ or north-bound group

- 28000 Lt Frank Campbell Vanrenen, Federated Malay States Volunteer Force.

- 225884 Lt Ronald Graham, Federated Malay States Volunteer Force.

- 68285 2nd Lt William Percy Harvey, Federated Malay States Volunteer Force.

- EC1888 Capt. Bernard Cunningham Hancock, 2nd King Edward VII’s Own Gurkha Rifles (The Sirmoor Rifles).

- IA/1081 Capt. David Richard Nugent, 2/18th Royal Garhwal Rifles.

MacDonald’s unofficial or south-bound group

- 178 Capt. Giffard Douglas ‘Mick’ MacDonald, Kedah Volunteer Force.

- VX34637 Sgt Joseph Kenneth Bell, AIF, 2/4th Anti-Tank Regiment.

- 954599 Flt Sgt J.R.H. ‘Jan’ van Crevald, Netherlands East Indies Air Force.

I am also satisfied that the three members of the unofficial or south-bound group were from Reg Newton’s “Australian wing”, also referred to as ‘D’ Coy.

Before moving on from this list, I should point out that the first postwar writer I encountered who got the escapees’ details correct was Lynette Silver and I am convinced her chief source was a section of a remarkable report named after Maj. R. Steele. (That report is held by the AWM and listed in the references below.) The section of that report relevant to the Pudu escape (pp.65-69) was written by Pte R.K. ‘Jock’ McLaren, a most remarkable individual, [see the review of Hal Richardson’s biography about him in the Reading page on this site] who listed all eight escapees correctly and knew that they consisted of two separate groups rather than a single party. How a private soldier got those details right in March 1944 when others, who were significantly better placed and of higher rank couldn’t do the same, is yet another mysterious element in this intriguing tale. It is possible the explanation could be found in McLaren’s earlier escape with two mates from Changi on 18 February 1942. After that breakout, McLaren and his comrades spent time with Chinese guerillas in a jungle camp between Kluang and Yong Peng before being recaptured on 12 April 1942. McLaren and his mates survived because they were able to convince their Japanese interrogators they were stragglers left behind by their units during the January fighting on the Malay peninsula. McLaren then went on to escape successfully from Berhala Island on Borneo, but then that is another story.

So, to return to the Pudu escapees, the north-bound party was led by Frank Vanrenen, a Malayan planter who had served with the FMSVF but then joined a unit designated 101 Special Training School which was a late addition to the battle plans for Malaya and sought to train ‘stay behind’ parties should the worst come to it and invading Japanese forces over-run the defenders. Given the ease with which the invading Japanese were able to roll through Malaya and capture Singapore, it might seem obvious now to plan for such a contingency but that was certainly not the prevailing orthodoxy in Malaya Command prior to the outbreak of hostilities and it was only in November 1941 that this under-resourced and under-prepared operation began. The most famous member of 101 STS was the then Captain Freddie Spencer Chapman, author of the classic memoir, ‘The Jungle is Neutral’.

Frank Vanrenen photographed probably at his rubber estate in northern Perak.

SOURCE: Steve Snelling ‘Far East Escape.’

Ronald Graham and Bill Harvey had also been part of Vanrenen’s ‘stay behind’ party before escaping to Sumatra and returning to Singapore on the eve of its collapse. Undeterred by their hasty departure for Sumatra and the difficulties associated with their return to Singapore, this intrepid trio went north again to assist Chapman. They were with Chapman in the period he referred to as his ‘mad fortnight’ when he embarked on a programme of sabotage and destruction of Japanese equipment and captured railway infrastructure and rolling stock. Others less charitable might refer to this fortnight as the only effective fortnight Chapman was to spend in the northern Malayan jungle for the next three years. But that is a story in itself and such a controversial claim it is best I go no further with that discussion here. Perhaps it could be the subject of a subsequent article. Suffice it to say that Japanese reprisals on locals for any acts of sabotage committed in their area were so savage that, according to both Braddon and Harrison, Vanrenen and Graham voluntarily surrendered to the invaders to avoid further bloodshed. Harvey had been captured earlier and these three comrades-in-arms were then reunited in Pudu early in April 1941. They avoided the gentle ministrations of the kempeitai by doing as McLaren and his mates had done and that is passing themselves off as stragglers from regular units in the area.

In mid-July, from his jungle camp in northern Malaya, Freddie Spencer Chapman sent a message through sympathetic contacts to Pudu urging his former colleagues to break out and join him in his guerilla campaign. In his memoir, Chapman makes no reference to this but that does not convince me it didn’t happen; on the contrary, it leads me to conclude this is probably a detail recollected correctly by those who survived incarceration in the Kuala Lumpur jail and that Chapman rightly felt a heavy sense of responsibility for conveying this message which was ultimately a death sentence for his three comrades, their two associates and even perhaps the three members of the south-bound party. It would be wrong to make too much of this since that is the nature of war and one of the later casualties of that war was Chapman himself who, after a remarkable and active life, committed suicide in 1971 at the age of 64.

In the light of the message received from Chapman, Vanrenen sought from Pudu’s senior British officer, Lt-Col. G.E.R. Hartigan of the 2/18th Royal Garhwal Rifles, permission to escape. Hartigan consulted Reg Newton’s cellmate, Lt Kenyon J. ‘Ken’ Archer, FMSVF, and both recommended against it. Archer had learnt the Japanese had introduced a ‘grid system’ which divided Malaya into areas with a ‘head man’ given responsibility for every zone. According to this system, if escapees or collaborators were found in any zone, the head man was responsible and reprisals would follow. In addition to the stick, the carrot was bounty money for any local who turned in an escapee. Vanrenen and Harvey were not dissuaded by this or the fact they would have a week-long trek through hostile territory to reach Chapman and, despite the best efforts of their superiors, they remained determined to go. They could speak the language, they said, had extensive knowledge of the area and contacts on whom they could rely. These arguments must have been persuasive because their party expanded to five with the addition of two late-comers: Captain Bernard Hancock, an ex-planter who had joined the Gurkha Rifles, and Captain D.R. ‘Dick’ Nugent, of Hartigan’s own unit, the 2/18th Royal Garhwal Rifles.

Freddie Spencer Chapman on the right with an unnamed Sig. on the left and the famous commando,

Brig. ‘Mad Mike’ Calvert.

SOURCE: 2/2 Commando Association, Australia.

As for how the second party led by MacDonald came to be involved in the escape, that could be a chapter of its own and it was a development which caused a great deal of acrimony at the time and later left a residue of bitterness and ill-feeling. All three of the men in this ‘unofficial’ south-bound party were members of ‘D’ Coy or what is also referred to as “the Australian wing” and this is where the Reg Newton connection comes to prominence since ‘Roaring Reggie’ was the officer responsible for ‘D’ Coy—which included thirteen members of non-Australian forces: two Dutchmen, some Malayan Volunteers (both FMSVF and SSVF), a Kedah Volunteer and one Kiwi. In the lead-up to the escape, there was concerted activity, most of it proceeding without the knowledge of the vast majority of the POWs. As the result of a “flurry of messages” sent through contacts at the local market, a rendezvous was arranged after the break-out between Vanrenen’s team and a band of Chinese guerillas at Rawang, 32km to the north. Reg Newton, the electrical engineer, was assigned the task of shutting off the electricity to cover the escape. Newton and Archer also took responsibility for concealing supplies that were gathered over the following weeks including native clothing, food and grenades. These supplies were hidden inside a waterproof container placed in a fountain in the prison’s hospital quadrangle; the Japanese had allowed the POWs to put the fountain back into working order. Newton set up a radio watch to listen for messages from Chapman. In addition, an elaborate scheme was devised to secure a copy of the key to the side gate that led to the vegetable garden.

The break-out was set for the night of 13th/14th August but, at about 1730hrs, an Australian sergeant of the 4th Anti-Tank Regiment, Ken Bell, who was a member of MacDonald’s group, approached Newton to “seek permission” to break out. Originally this group was to have included L/Sgt Clarrie Thornton, also of the 4th AT Reg, but Thornton had a severe attack of dysentery and so the other three ruled him out—a stroke of luck so bad it saved his life.

Reading between the lines in this part of the 2/19th’s account, it seems likely that Bell approached Newton as the CO of the mainly Australian ‘D’ Coy out of a sense of loyalty because he was the only AIF soldier in the party and MacDonald, who was the leader of this wildcat group of three, had intended to abscond without letting anyone know; what is less clear and is a matter which confused at least two and probably three highly-credentialled historians is that van Crevald and MacDonald were both residents of “the Australian wing”.

As for anti-tanker, Sgt Ken Bell, he had originally been captured by the Japanese 24 hours after a last-minute decision to put him and his gun in reserve at Gemas on January 14th; he never fired a shot in anger. As Ken Harrison explains:

“Bell and his crew …, after having their arms bound behind them, were made to sit on the earth floor of a hut. During most of the following day they were savagely beaten by Japanese tank crews as a reprisal for the mauling we had given the First Tank Regiment.”

It is interesting that Mick MacDonald, a captain, would choose for fellow travellers two NCOs. The inclusion of Clarrie Thornton in the original plan suggests that as anti-tankers Bell and Thornton were mates; perhaps a friendship had been struck between them and the expatriate Australian, MacDonald, but the cause for such a connection does not leap from the record; Bell was a Melburnian and Thornton was from rural Berrigan in NSW; MacDonald was a Duntroon graduate, originally from Sydney’s north shore, until recently a privileged colonial planter and now a Kedah Volunteer of the officer class. Of course, the source of the connection could have been the handsome Jan van Crevald, who spoke Malay and had entertaining tales of his life in the Dutch East Indies prior to the war. There is evidence Bell and van Crevald shared a cell. It is also possible van Crevald was an officer posing as an NCO.

One of the Pudu chroniclers, L/Sgt Ken Harrison, was also a member of the 4th A/T Reg. and, as such, was good mates with L/Sgt Clarrie Thornton and Sgt Ken Bell. He was not included in the party because he had been shot in the ankle prior to his capture at the end of February and, in August, was still recovering. This exclusion clearly barred him from participation in conversations about the breakout in the lead-up to it. His claim that Thornton and van Crevald were added to the escape group by Vanrenen to “ensure an adequate crew for the voyage across the Indian Ocean” was so far wrong as to suggest he was not privy to any of the planning discussions and, to fill the gaps in his knowledge, had to rely on the Pudu rumour mill which was active at any time and must have been running hot after the escape. Interestingly, enlisted artilleryman, Russell Braddon, claims there was a “tentative suggestion” that he “join the escapees” but that was abandoned because he “had fair hair of a conspicuously un-Malayan hue”. Still, that suggestion must have been very tentative because his account of the escapees’ plans was just as wide of the mark as Harrison’s. One of the other eye-witness accounts is by Pte Alex Drummond of the 2/29th Bn, who kept a diary during his time at Pudu and throughout the three and a half years of his captivity. However, his diary reveals no prior knowledge of the plan—perhaps because doing so would have been disastrous had his journal been found but more probably because he also was not a party to the earlier discussions. On August 14th, the morning after the escape, his comment was: “we have had a big surprise this morning”. His later entries only confirm that with regard to the formulation of these plans, he was an outsider.

So now at 1730hrs on the night the carefully orchestrated ‘official’ escape led by Vanrenen was to occur, Reg Newton was told by Ken Bell that Mick MacDonald was planning an ‘unofficial’ escape with the intention of heading south to Malacca where “his old rubber plantation” was located. Newton described this news as “an absolute bombshell”. Hours of intense negotiations followed. By the time Vanrenen and Harvey were brought in, it had become an “acrimonious and bitter discussion”, one which was to last almost until midnight. Clearly a great deal of pressure was brought to bear but, as the 2/19th’s history puts it, MacDonald “would not budge and all he kept on saying was that he had arranged to go that night. When told about the grid system he said this was mentioned just to stop him from going out and that he did not believe Ken Archer about the grid idea.” Ken Bell was approached by Newton but also refused to budge. Vanrenen implored MacDonald’s party to postpone their departure for one night since his was an official escape and theirs was not. Not surprisingly, MacDonald did not concede on this point either—doing so would surely have spelt doom to his plans but saved their lives—and so both parties broke out a short time later, no doubt mentally exhausted from the outset thanks to this dramatic heightening of an already tense situation.

The precise time of the breakout is yet another detail that is unclear with one account saying it occurred at 10:00pm and another saying midnight but, given the number of references to the escape occurring on August 14th, I am inclined to favour the midnight option. Capt Mick MacDonald’s letter says, “We broke jail on the evening of the 13th August.” The distance travelled before trouble struck adds support to the notion that, if the breakout took place before midnight, it was not much before. Mick MacDonald’s group was the first to get into trouble and that occurred at 2:00am on the morning of 14th August near the 5-mile peg from Kuala Lumpur on the Kajang Road—a distance of 7km from Pudu.

To conceal the absences, Brune says roll calls were manipulated “for the agreed time” but what that was in practice is once again shrouded in doubt and confusion. Based on the eye-witness testimony of New Zealand officer, Lt Pat Garden, Audrey Holmes McCormick argues strongly that the agreed period was one day: “it was decided to fake two roll calls the next day, bringing in prisoners who were normally ill”—meaning the ducks and drakes were played at one morning and one evening roll-call or tenko.

While that differs from some accounts, including that of another eye-witness, Pte Charles Edwards, it is sufficiently consistent with other evidence to be persuasive. So it was that on the morning of August 15th, the Japanese corporal responsible for the ORs’ tenko, the mostly harmless ‘Frogface’, went away to report his count had come up short, expecting a beating as his reward. He came back smiling because, whereas he was missing two, the officers were missing six. This was the signal for the Japanese to storm into the lines and make a great ruckus as they called all POWs out for a more careful tally of numbers. In the Australians’ wing, they were particularly savage on WO Carl Renkert and Reg Newton, beating both in front of the assembled troops.

From here, the precise details of this episode, which were hazy before, become positively murky. However, as Mick MacDonald’s unfinished letter reveals, his party struck trouble when they passed a small wooden shack and set a dog barking. They were challenged by a man from the shack and scattered. The shack’s occupant blew a whistle and people appeared immediately. This was not normal behaviour and, as Silver notes, it shows the grid system was “working with great efficiency.” MacDonald dropped his pack and ran. Bell and van Crevald were caught and brought back to Pudu at midday on August 15th. Pudu inmates saw the two fugitives brought in and locked in an upstairs cell. Alex Drummond reports that he was able to smuggle cigarettes and matches to them on at least two occasions but the risk involved was considerable so he discontinued these efforts after September 6th.

As for Mick MacDonald, he spent the day of August 14th, hiding on a hillside. From there he made his way to plantations where he had trusted friends and associates, making it as far as the Tampin Linggi Estate, near Port Dickson and about 95km south of Pudu, before being captured on August 30th. POWs working in Kuala Lumpur saw him on September 3rd. At that time he was with “a group of native prisoners” being marched into Japanese headquarters. He was returned to Pudu next day. The bounty paid to each of two dodgy Malays who assisted with his re-capture was $2. A Malay policeman received $10. That was the price of a life in the area controlled from the recently renamed, Syonan, or “light of the south”.

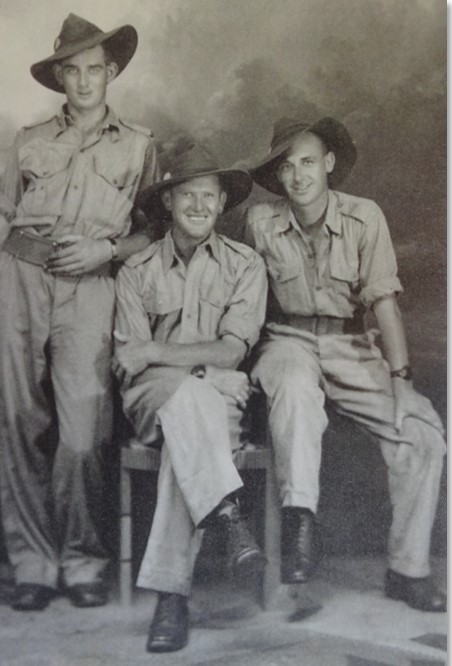

VX52775 Pte Alex Drummond (right) with two unnamed mates,

presumably, like him, from the 2/29th Battalion.

SOURCE: Alexander Hatton Drummond. ‘Papers, 1941-2001.’

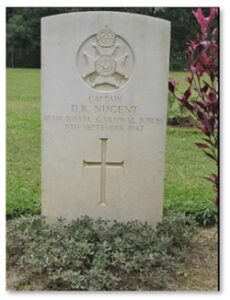

There are also conflicting details and versions related to Vanrenen’s party. The 2/19th’s history states that most of them were picked up within 48 hours of the breakout, having reached Batu Caves which is only 15km from Kuala Lumpur. A very specific story is then told about the fate of the Indian Army officer, Dick Nugent. According to this account, he was cornered and wounded on a rubber plantation near Rawang further north. One of the Indian estate workers there was made to dig a grave with Nugent watching and waiting for his own execution which followed shortly after. The consensus of opinion and most of the evidence indicates that that story is wrong and that Nugent was returned to Pudu and confined to the ‘hospital’ there where he died between September 11th and 13th but I am going to go out on a limb and say that is also wrong. The reasons for doing so are outlined below.

Lynette Silver tells us Vanrenen’s party ran into trouble “early in the piece” and had to fight their way clear of “shotgun-toting Malays”. From that point they made their ways separately to an agreed rendezvous with Chinese guerillas “near Batu Caves” but the Japanese, who were tipped off, surrounded the area in the early hours of the morning of September 1st. In the fighting that ensued, seven guerillas were killed. Subsequently their leader’s severed head was taken to Kuala Lumpur where, in the inimitable IJA fashion, it was placed on a pole for the edification of the viewing public. There were at least two more armed skirmishes before the last of the group was captured “at Batu Caves”. The date of their capture is not given but they were brought back to Pudu on September 7th. While they differ on his fate, Silver and ‘The Grim Glory’ agree that Capt. Dick Nugent was captured 15km north of the others at Rawang.

Upon their return to Pudu, the escapees were placed in cells above the guard room where the kempeitai set to work on them. They were beaten and tortured for days in efforts to extract information about the Chinese guerillas with whom they had co-operated. Surely it was no accident that every prison inmate got to “hear the whole terrible treatment”.

On the morning of September 16th, officers were allowed briefly to talk to the re-captured men. Prior to that POWs had seen them being moved about but were prevented from coming near or speaking to them. Some messages had been passed on by cooks and, as we have seen, Alex Drummond was able to make his way to Bell and van Crevald’s cell on two occasions. On this, their last morning alive, the officers were visited by Ken Archer while Reg Newton talked to Ken Bell and Jan van Crevald; they were allowed only fifteen minutes together. The seven survivors held no illusions about their fate. They asked for final messages to be passed on to their families and members of the northern group made it clear they blamed MacDonald for their capture. The writer of this section of the battalion history—almost certainly Newton himself—rates this “a very fair comment” then, in a masterful display of understatement adds that “MacDonald showed an error of judgement.” Of course, he was not the only one. These hurried final moments were:

“very emotional and disturbing, and probably Bell and Van Crevald were more tranquil than Newton was. All of them were taken downstairs and placed on a motor truck after farewells had been exchanged, and picks and shovels were noticed on the tray of the truck.”

Ken Harrison provides this moving description of the fatal departure of these seven escapees who:

“were brought to the jail entrance, where a military truck was waiting. They were bound hand and foot and were obviously very weak. A guard motioned them to get on the truck. As they sat there Van Rennan pointed with his foot to their haversacks that lay heaped on the ground. The answer was a death sentence, ‘Nei.’ There could be only one reason why they would not require their belongings and every man present knew it with a stabbing clarity.

“For a few long minutes we stood staring at the eight [sic] bound men. Twice I tried to call to Ken Bell, “See you in Singapore, Ken,” and twice I got as far as “See—” and could not go on. We smiled, but our smiles were strained, and as the big gates swung open and the truck jerked forward, there was little hope in our hearts.”

The escapees were driven to the Cheras Road Cemetery, made to dig their own graves and shot.

And that ends the first section of this article. Beyond this point, as mentioned, the material is recommended only for the fully committed. It examines a number of the conflicts and questions over these events, namely:

- Conflicting Evidence on the Identities of the Escapees

- The Search for Precise Details on the Identity of Dutch Flt-Sgt Jan van Crevald.

- Confusion Over the Timeline

- Conflicting Versions of the Tenko Subterfuges

- Conflicting Evidence Over the Number Executed at Cheras Rd Cemetery

- Confusion Over the Fate of Dick Nugent

CONFLICTING EVIDENCE ON ESCAPEES’ IDENTITIES OF ESCAPEES

The problem of the identity of the escapees was really my first insight into the complexity of the stories surrounding this escape. That there were eight escapees is one point on which all the accounts agree. However, two of the three accounts written by eye-witnesses—Russell Braddon and Kenneth Harrison—state that eight men were put on the truck that went to Cheras Rd Cemetery on the morning of September 16th. ‘The Grim Glory’ gives a list of the eight who escaped but it does not state a number who were put on the truck; it also includes a mysterious ex-planter identified only as “Morrison” as part of the original eight and tells the story of Nugent’s execution referred to above. In her work on POW leadership, Dr Katie Meale referred to two Australians being amongst the escapees—which is right—but stated that Mick MacDonald was British—which is wrong. Historian Peter Brune refers to Nugent’s death in prison but doesn’t name him. Brune then refers to eight men being loaded onto the truck. In so doing he was probably misled by the eye-witness accounts of Harrison and Braddon, which he cites, even though his main source for this section is Lynette Silver and she does not specify the number on the truck and is very clear about Nugent’s fate; so clear, in fact, that she says Dick Nugent is the only escapee to have a marked grave, a point confirmed by other sources. The War Graves Commission website provides conclusive evidence for Silver’s version showing Nugent’s date of death as 11th September 1942. His grave is in the Taiping War Cemetery. If my reading of the records is correct, his plot is No.104, possibly in Section B12, but the details given on the cemetery plan are: 1595/1/A/8, 4.B.12, 104. Whatever the precise details of Nugent’s death may be, what can be stated with confidence is that seven men—not eight—were loaded onto that truck on September 16th and executed at the Cheras Rd Cemetery. Confirmation of the identities of the eight was further compounded by confusion over the numbers in ‘D’ Coy or “the Australian wing”. According to the Pudu section of ‘The Grim Glory’ which was no doubt substantially written and certainly edited by Reg Newton, there were 185 POWs in his part of the prison and he “lost 3 executed and five from disease”. In 1985 Dr Hank Nelson repeated that summation in his work dealing with the recollections and stories of survivors: “only five died out of 185 in the Australian wing and another three had been executed.” At least part of the explanation is that not all those in the “Australian group” or “Australian wing” [terms used interchangeably in the unit history] were Australian and the three executed were Sgt Ken Bell, AIF, Capt. ‘Mick’ McDonald, expatriate Australian and Kedah Volunteer and Flt-Sgt Jan van Crevald, NEIAF. For the record, it needs to be stated that the number of Australians who died of wounds or disease in Pudu was not five but six. As for the figure of 185 given for the “Australian wing”, that does not match numbers given elsewhere; the verifiable figures given in the history provide a total of 178. So one may be forgiven for having here the sensation of sand shifting constantly underfoot. But the records are what they are and human memory is what it is.

Conclusions

In terms of giving the identities of the escapees, the most accurate account I have read was and remains, as mentioned above, Lynette Silver’s but putting myself in a position to write that throwaway line has taken an unspeakable number of man-hours and cogitation. As for the conclusions reached on the subject of the escapees’ identities, they are shown in the section above where the names and details of the individuals are given. Because of the information available at the CWGC, this is one area about which I am confident of accuracy. Outstanding questions related to Dick Nugent and Jan van Crevald remain but these do not detract from the reliability of the information given here and both the Nugent and van Crevald questions are dealt with below.

PRECISE DETAILS ON JAN VAN CREVALD

Determining the precise identity of Jan van Crevald and locating his regimental details has taken the better part of three years and the result I have now is one I regard merely as a tentative solution. Little bits of information about Jan van Crevald are given by different sources. Fortunately, ‘The Grim Glory’ is one of the sources that gives his surname as is the digital nominal roll for Pudu available through the ‘Find My Past’ website. Braddon and Harrison refer to him only as “Jan”. Harrison describes him as “a handsome and light-hearted Dutchman”. Both Harrison and Braddon also tell the story of van Crevald’s remarkable escape from a burning Vildebeest. According to Braddon, Jan’s aircraft was in flames and he was without a parachute so:

“He had climbed to the tail of the blazing plane—the only portion not alight—and when it struck the earth, he had been catapulted hundreds of feet through the air into the soft foliage of the top of a high jungle tree. He had climbed down unharmed and wandered round for a few days until eventually he found his [badly burned observer, Flt-Sgt van der Made].”

At Pudu van Crevald was a popular Dutchman because he spoke “perfect English” and was a great raconteur who regaled POWs with droll tales of his time in the East Indies. On work parties POWs dreaded the terrors of transportation in over-crowded Marmon-Herrington trucks and, on Friday July 24th, there was a crash with a standing-room-only load on board. Drummond records that van Crevald escaped this calamity with only “abrasions on the leg & stomach”. In consequence, Harrison says, “Jan was generally agreed to be lucky”. Unfortunately, his luck ran out on this bid for freedom.

As mentioned, finding details in the existing record confirming the identity of Jan van Crevald has been challenging and remains an unfinished task. According to the version of this episode Pat Garden told Audrey McCormick, van Crevald was a Dutch captain concealing his identity and posing as a sergeant. In 2012 Pte Charles Edwards as a 93 y.o. wrote a response to McCormick’s article in ‘Apa Khabar’, the magazine of the Malayan Volunteers Association. In it he told the story of van Crevald’s first day at Pudu when he met the RSM from the 2nd Argylls, WO1 ‘Jock’ McTavish. As Edwards tells it, new arrivals were asked to state their rank and name. Van Crevald introduced himself as “Brigadier Jon Van Crevald”. On hearing this, McTavish snapped to attention and saluted. Jan then told him, “in the Dutch Air Force brigadier is equivalent to a corporal”—which amused the other men lined up on parade but proved something of a letdown for the RSM. I suspect this may have been the source of the story about van Crevald concealing his true rank. However, while Edwards’ comments and information are interesting and come sufficiently late in the discussion to be informed by most of what had gone before, it cannot be relied on entirely since, in that same contribution, he tells a story related to his and Ken Harrison’s capture which can only be accepted if much of the first part of Harrison’s own memoir—which covers time spent with Chinese guerillas and his wanderings through occupied Johore—is dismissed as fiction. Since that seems extremely improbable, the inescapable conclusion is that even that remarkable survivor and conscientious custodian of the Australian POW legacy, Charles Edwards, must be included in the long list of imperfect witnesses. Sadly, such are the vagaries of human memory.

The redoubtable Pte Charles Edwards

photographed at Ohama #9-B.

SOURCE: The QLD Numismatic Society

Conclusions

The details I have for Jan van Crevald are listed above in the section showing the identities of the both escape parties but I will repeat them here:

954599 Flt Sgt J.R.H. ‘Jan’ van Crevald, Netherlands East Indies Air Force.

I must say that the regimental number shown comes from a search on the ‘Find My Past’ website which has an electronic list of all the POWs interned in Pudu Prison. I have yet to find any corroboration of that. In the process of identifying the Dutch member of the escape party, I emailed the Dutch National Archives and got a great response but, unfortunately, no result. I then sought the help of a Dutch researcher named Henk Beekhuis and really want to acknowledge prominently here the assistance he provided—even though it also produced no results—but that was not from want of trying. Henk searched a number of sites including a register of the RNEIA, Dutch war graves and a digitised collection of Japanese internment cards. He described his skills in this regard as very good but was unable to turn anything up. Thanks to the miracle that is Google translate, I have searched a number of Dutch sites in a variety of ways using the rough date of death, the regimental number and a variety of spellings of van Crevald [sometimes written as van Crevold but most probably spelt Creveld or Kreveld] and returned nothing. The story which I cannot verify and which appears questionable—especially in light of Charles Edwards’ clarification of its probable origins—about van Crevald concealing his true identity may have something in it. What that is at this time I cannot say. However, the fact that no official references to Jan van Crevald can be found is more than a little perplexing. My experience has been when so many different searches turn up so little information, something is wrong with the original search data. The search process is complicated by van Crevald’s Dutch nationality and the language issues that result but I retain a strong suspicion that more of this part of the story remains to be told.

CONFUSION OVER THE TIMELINE

For some time my best hope for answers to questions about the escape timeline was reading Alex Drummond’s original diary which is held in the State Library of Victoria. Being written in a day-by-day format, I thought it would resolve once and for all much of the confusion and conflict over these events. Unfortunately, Drummond’s account proved significantly less definitive than anticipated. For instance, he gets crucial details wrong as is shown by his inaccurate description of the escapees’ departure in the truck that took them to their execution at the Cheras Rd Cemetery. He dated that entry Friday 19th September whereas the Friday in question was September 18th. He also referred to the escapees leaving “last night” which would mean their departure in the truck occurred on the evening of Thursday September 17th when, in fact, it occurred on the morning of Wednesday September 16th.

Drummond’s material also suggests the absence of Bell and van Crevald was discovered on the morning of August 15th, meaning the tenko subterfuge was attempted on August 14th and may have been attempted on the morning of August 15th but did not then succeed. Of course, tenko occurred morning and night, as Drummond’s entry for August 16th shows. So that would mean the roll-call ruses worked twice and failed once. It may be drawing a long bow, but is it possible that a source of confusion here is between the number of tenko manipulations and the number of days on which it was done? Given that Drummond’s tidied up version of his diary, ‘The Naked Truth’, states that the shortfall at tenko was discovered on the first morning after the escape, that seems unlikely.

Conclusions

It would be great if Silver’s timeline were correct but it is not in all respects. For instance, she claims the roll-call errors were discovered on August 16th and I am convinced that is wrong. Moreover, I cannot see how she came upon the timeline she has constructed and my attempts to ‘reverse-engineer’ it from her sources have not succeeded. The tenuous grip I had on the facts of this story would have been tightened if diarist, Alex Drummond, were a more reliable witness—but he is not. While his Pudu journal is structured as a day-by-day account, there is no firm evidence it was written daily and, when the executions occurred, he was bed-ridden with ‘happy feet’. In ‘The Naked Truth’, Drummond says that Gnr Reg Dudley, 2/15th Fld Reg. took over writing his diary in the period when the events that followed the breakout occurred. In that later manuscript version, Drummond changes his timeline but, in doing so, makes it less accurate than the diary version, claiming the executions occurred on the night of September 19th. It seems even a person who was there cannot fully agree with himself. As a result, the timeline I have proposed is the best I can construct based on deduction from the evidence available. I regard it as a working hypothesis rather than a done deal.

CONFLICTING VERSIONS OF THE TENKO SUBTERFUGES

The 2/19th’s history states that to conceal the escape, numbers at tenko were manipulated for three days (“next morning…and for the next two days”) but that claim is internally inconsistent since it is stated elsewhere that Vanrenen’s party was captured within 48 hours and Bell and van Crevald “were picked up about the same time”. Harrison says “our friends…were back in the jail by midday”, i.e., on August 14th. Braddon’s account supports this; the tenko subterfuge “was achieved only once”. While that seems unequivocal, it isn’t. Their comments would make sense if both were referring only to the two NCOs from the Australian wing, Bell and van Crevald, but that does not marry with remarks elsewhere. Brune says the first captives were returned to Pudu within 36 hours; Silver says it was more like 58 hours. However, because Brune’s account is based on the false premise that the escape occurred on the night of the 14th/15th, he agrees with Silver that the first escapees were returned about midday on the 16th. He says van Crevald and Bell spent only one night at large. According to Silver’s timeline, rolls were manipulated on the mornings of August 14th and 15th; the shortfall in numbers was discovered on the morning of August 16th. Silver’s account does not explain where Bell and van Crevald had been in the interim between their capture and return—from early August 14th to midday August 16th—but nor does any other account; each has gaps of varying duration. Braddon and Harrison’s recollections make the gap the shortest but accepting their versions means throwing out a lot that is stated unequivocally elsewhere. Also, for what it’s worth, I suspect that, when Harrison was writing his 1965 account, he referred closely to Braddon’s 1953 memoir and that Braddon’s construction may have either influenced or misdirected his version. The most likely explanation for the delay between Bell and van Crevald’s capture and their return is that in the interim they were detained at kempetai headquarters in Kuala Lumpur as MacDonald later was. But, for that to be the case something extraordinary must be accepted and that is that the kempei commander in Kuala Lumpur did not pick up the telephone and ask the Pudu commandant if he were missing any prisoners. Yet, for all its improbability, it seems something like that occurred because it was not until the morning of Saturday August 15th that Drummond reported the guard-house phone was “getting a hiding”. Unless we accept that failure to phone or inform, Braddon’s and Harrison’s timeline must be adopted, according to which only one tenko was falsified and Bell and van Crevald were returned to Pudu around noon August 14th. But, if that summary makes the options appear to consist of a simple either/or choice, then it’s misleading.

It makes sense that the absences were discovered on the morning of August 15th. It was later that same day that the phone got a hiding. According to Drummond the discovery was made at the MORNING roll call. While Drummond gets days and dates wrong, surely when writing very close to the events, he would remember whether such a flap occurred in the morning or the night. McCormick is VERY clear that the discovery was made on the MORNING of August 15th. According to the Pat Garden version as told by McCormick, officers deliberately went out of their cells and left the garden gate ajar the night after the escape to make it look as if the escape had occurred a day later but this deception failed because the escapees didn’t stick to the agreed story when recaptured. However, this is inconsistent with claims that the roll-call ruse was to continue for 48 hours as there would have been no point in the ruses continuing a full day after the gate had been left open. Garden also had a theory that the camp commandant didn’t want the kempeitai to know the actual date of the escape and that there was an unspoken agreement or collusion between Garden and the commandant on that score.

Silver and Brune had the advantage over this writer of interviewing survivors but they did so more than sixty years after the events. Neither of their versions agrees with the accounts of Harrison and Braddon but, by that token, those accounts differ from two of the other primary sources—Drummond and the 2/19th’s history. According to Drummond’s entry for Saturday August 15th, “The roll-call this morning was rather a lengthy affair owing to the fact that by some mysterious means 2 of D. Coy Sgts. were missing 6 officers.” This is a cryptic entry and the reliability of these comments is not enhanced by Drummond’s confusion over dates at this time. Nevertheless, on Sunday August 16th, he wrote:

“we at last made out that the escapees had been captured & had stated that they had escaped on the night of the 13th. Bell & Van Crevald were up at the guard-house but apart from them no authentic news could be gathered although rumour has it that Nugent is in hospital & 3 others are dead.”

This reference to Dick Nugent is puzzling. The rumour that “3 others are dead” is dealt with easily because, like most rumours Drummond reported, it was wrong. But why is Nugent singled out for mention and why on August 16th when, according to Silver, Vanrenen’s party did not rendezvous with Chinese guerillas until September 1st? Surely, this is no coincidence and yet Silver’s timeline does not have Nugent back at Pudu until September 7th and Drummond himself did not report Nugent’s physical return until September 9th. This is a mystery in its own right and so discussion will return to it shortly.

Writing in 2012 as a 93 y.o. in response to Audrey McCormick’s article in the Malayan Volunteers’ magazine, Charles Edwards gives some very clear and precise details of what he called ‘The Count Fiddle’. He states that the intention was to continue the ruse for 48 hours but that the discovery of the shortfall in numbers was made on August 15th. While he does not state whether the discovery occurred in the morning or the night, the diary of Alex Drummond shows it must have been the morning of that day. In addition, it seems clear that Bell and van Crevald were returned to the prison at midday on August 15th. This timeline makes sense of a number of otherwise inexplicable inconsistencies and conundrums surrounding the breakout. While it is a chronology that differs from others given in personal recounts and subsequent histories, it is the only one that has so far made any sense to me. I could go round and round on this point alone and shed readers with every sentence I write but let us for now lock in that date and time for the return of Bell and van Crevald. As mentioned, they had been captured only a couple of hours after they left Pudu and then spent a day somewhere, most probably at kempeitai headquarters in Kuala Lumpur, where it is certain their hosts did not offer them tea and cake.

A strange detail is that the tenko subterfuges must then have succeeded twice after the escapees were recaptured. I openly acknowledge the incongruity of this claim. It would not have required the intervention of a Japanese rocket scientist to work out whence two Allied soldiers captured in occupied Kuala Lumpur had come. It was by then seven months since the whole of the Malay peninsula had been over-run and Caucasians in Malaya stood out like beacons. The organisation of the IJA was noted by POWs as being extremely compartmentalised but even acknowledging that, it seems ridiculous a telephone was not picked up and contact made with the commandant at Pudu. Moreover, the kempei in the city centre could easily have phoned the kempei at Pudu who were set up there at that time and engaged in vigorously ‘interrogating’ suspect Chinese. For all its improbability, that certainly seems to have been the case and it was not until after discovery of the tenko shortfall that Alex Drummond reported the guard-house phone was “getting a hiding”—and that was the morning of Saturday August 15th. The best justification I can provide for this interpretation is that it relies on the action of human error and we all know the extraordinary scale and number of things humans are capable of getting wrong. We could build whole empires on this capacity if only we could harness it for good; on the other hand, I am sure it has brought empires down just as it has sunk huge ocean liners, crashed the most sophisticated passenger jets and caused nuclear reactors to meltdown.

Audrey McCormick advances Pat Garden’s theory that the commandant of Pudu didn’t want word of the escape spread, nor did he want the kempeitai commander in Kuala Lumpur to know of it. As a result, when he was taken away for interrogation and then punishment for his part in the preparations for and subsequent cover-up of the escape, there was some form of unspoken collusion between Garden and the camp commandant so that the tenko manipulations were not mentioned and the myth was maintained that the escape occurred on the night of August 14th/15th. Unfortunately, that makes no sense since Bell and van Crevald had already been picked up at 2:00am on August 14th. Finding a way through so many conflicting details is not easy nor is understanding the strange delay between the recapture of Bell and van Crevald and that news being conveyed to Pudu.

Conclusions

I see it as significant that Garden’s understanding with the Pudu commandant was an unspoken one and as such that leaves a gap wide enough for several trucks, a column of elephants and a llama or two to be driven through. However, the delay definitely occurred and a strange kind of illusion was maintained that the breakout happened a day after it did so is it possible there was the potential for enormous embarrassment and loss of face on both sides—I mean both within Pudu and the Kuala Lumpur kempeitai—because the information of Bell and van Crevald’s re-capture had not been passed in a timely manner? Had that been done and a thorough count conducted in the prison, the absence of another six prisoners would have been discovered. MacDonald remained at large until August 30th and, according to Silver, Vanrenen’s party was not recaptured until September 1st. Is it possible the egg from that glaring oversight would have been sufficient to cover a great many faces, not just that of Pudu’s commandant? Could this then explain that strange hiatus between recapture and the flap inside the prison walls?

CONFLICTING EVIDENCE OVER THE NUMBER EXECUTED AT CHERAS ROAD CEMETERY

A fair part of the confusion on this subject has been dealt with in the section dealing with the identity of the eight escapees. Much of the difficulty arose over the eye-witness accounts written by Braddon and Harrison both stating clearly that eight men were loaded onto the truck that left Pudu on the morning of September 16th 1942. Peter Brune fell into this trap and states clearly in his account that eight men were executed at Cheras Rd Cemetery. As explained earlier, clarity was not enhanced by the reference at the end of ‘The Grim Glory’s’ section on Pudu which refers to three members of the Australian wing being executed. Katie Meale was one who misidentified Mick McDonald as a Briton; when coupled with her correct assertion that two Australians escaped, this certainly sent me down several unproductive rabbit holes. Nor did ‘The Grim Glory’s’ odd reference to a Morrison being in the escape party assist. His name is mentioned only once; no nationality, unit, initials or first name are given and the name does not appear in the index of that work. Of course, it is hard to be definitive when searching for details on a WW2 reference as vague as “Morrison”. However, two reasonable assumptions could be made: Firstly, if there had been a Morrison in the escape party, his date of death must be on or close to that of the other escapees. Secondly, the other escapees, with the exceptions of Nugent (who is listed elsewhere) and van Crevald (who is not listed at all), are listed on the Singapore Memorial. A search of war dead on that memorial with the name Morrison returns seven results. From the dates of death and the details for those seven it is clear none of them were amongst the Pudu escapees. In addition, there is no reference to any Morrison in the index to Chapman’s book. So, when coupled with the other evidence, it is reasonable to conclude that there was no “Morrison” in either party. Latterly, I am indebted to British researcher, Keith Andrews of COFEPOWs, for his assistance in revealing details of a Morrison who was in Pudu: 225859 2nd Lt. L. H. Morrison, 1st FMSVF. Morrison had been the Commissioner for Labour, Klang, Selangor. He left Pudu in October 1942 for Singapore, then went to Thailand as part of ‘H’ Force. He returned to Changi in November 1943. He passed away in Devon in 1985. It is reasonable to assume this is the individual mistakenly included in the 2/19th history’s list of escapees.

Conclusions

The reference to Morrison being an escapee is undoubtedly a misremembered name. The name not mentioned in ‘The Grim Glory’ is that of Capt. B.C. Hancock who, along with Nugent, was a late inclusion in the north-bound group. Every account is clear that Nugent was not one of those loaded onto the truck that drove to Cheras Rd and that he died some days earlier—as to where and the details of his demise, that is discussed in more detail in the following section. But this is a point on which we can be clear partly because Nugent is the only one of the eight to have a marked grave—and it is not at the Cheras Rd Cemetery. Therefore, it is with a great deal of confidence that I can affirm what others have said before: there were eight escapees but only seven were executed on the morning of September 16th 1942. Making that assertion requires repudiation of the specific references in both Harrison’s and Braddon’s accounts to eight men being loaded onto the truck at Pudu. That is as it is and, on this point, despite their best intentions, both were wrong. Their lack of accurate information should be balanced against the need at the time for secrecy in the escape arrangements and to Braddon’s status as a private soldier. As a senior NCO and a close mate of Bell and Thornton, one would have expected Harrison to have been more closely connected with the story but that clearly was not the case. This section of ‘The Grim Glory’ was almost certainly written by Reg Newton and, if not, would have been edited closely by him. As the senior Australian officer and cell-mate of Ken Archer, he was part of the inner circle. That doesn’t mean he would get every detail correct when writing of it 33 years later, as the Morrison gaffe shows, but ‘The Grim Glory’ is clear that eight men escaped and seven were executed at Cheras Rd, with Nugent not amongst them. In those respects, the unit history is accurate.

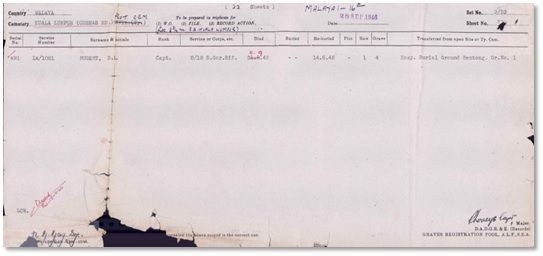

CONFUSION OVER THE FATE OF DICK NUGENT

As mentioned above, according to Silver, Vanrenen’s party did not rendezvous with Chinese guerillas until September 1st. She also states that Nugent did not return to Pudu until September 7th. However, Pudu diarist Alex Drummond did not report Nugent’s physical return until September 9th. And that sounds like convincing evidence showing that Nugent did return at some stage although precisely when may be subject to debate. The 2/19th’s history states that most of the north-bound group were picked up within 48 hours of the breakout, having reached Batu Caves which is only 15km from Kuala Lumpur. The very specific story of Nugent’s execution which was cited above is then told—an estate worker was forced to dig the grave while the wounded Nugent looked on and waited for his inevitable end. The consensus of opinion and most of the evidence indicates that this story is very wrong and that Nugent was returned to Pudu and confined to the ‘hospital’ there where he died between September 11th and 13th. However, it seems that none of the prisoners actually saw Nugent in Pudu. After stating that Nugent was in hospital there, Drummond acknowledges this was based on rumour and that he had not seen him being brought in or seen him in the hospital. Nugent’s official date of death is given by the War Graves Commission as September 11th but by other sources as September 13th. On the other hand, Audrey McCormick very clearly asserts that Nugent was confined to Bentong Hospital which is 68km northeast of Kuala Lumpur. McCormick is also clear that Nugent did not die of his wounds but was taken from hospital and executed. The CWGC website says Nugent was re-buried at Taiping on June 14th 1946 and adds the note under the heading “Transferred from open Site or Ty. Cem.”, “Hosp. Burial Ground Bentong. Gr.No. 1”. That I take as strong evidence in support of McCormick’s Bentong theory. This June 1946 re-interment of his remains explains why an individual who died at Bentong would be buried in Taiping, which is 266km north of Kuala Lumpur which was a detail that baffled me for at least three years. However, it has clearly baffled or simply been dismissed by others who have re-told the story of this escape. I am conscious reading this level of detail could be about as exciting as watching paint dry for most people. However, I find great interest in the information provided by that 1946 document now available on the CWGC website. I think it is hard to read that and support any other version of Nugent’s death than the one told by Audrey McCormick. I find it interesting that in reading Drummond’s ‘The Naked Truth’ manuscript, he states that Nugent was wounded in the leg and taken to hospital. Although there is no elaboration, this later version could be more true than most latterday writers have realised.

Conclusions

The CWGC information about Nugent’s death at Bentong means that ‘The Grim Glory’s’ story of his graveside execution was probably correct but happened significantly further north from the place originally thought by the Pudu inmates. The evidence showing that Nugent’s remains were exhumed postwar explains why he was not buried at Cheras Rd where other dead from the ranks of the Pudu POWs were buried, even if most, if not all, were later re-interred at Taiping War Cemetery. This evidence therefore throws into question—in fact I would say, refutes—the scenario promulgated by Silver and Brune. I am conscious that accepting this hypothesis means dismissing other evidence which appears unequivocal but that is the case with every construct of this story and what we must accept here is a kind of ‘best fit’ amongst the conflicting accounts. So, in that spirit, that is the theory I am proposing. It is proffered with all those caveats writ large and, if more evidence emerges, I will gladly recant—as I have done five or six times already in trying to put the pieces of this episode together. However, I take that 1946 CWGC document about Nugent’s re-interment to be very strong evidence indeed.

Information on Dick Nugent’s re-interment at Taiping War Cemetery.

SOURCE: The CWGC website.

That document (which I can’t seem to reproduce in a larger format) is available at:

https://www.cwgc.org/find-records/find-war-dead/casualty-details/937737/david-richard-nugent/

Taiping War Cemetery

SOURCE: The CWGC website

The grave of Capt. Dick Nugent,

Taiping War Cemetery.

SOURCE: Findagrave.com

FINAL COMMENTS

So there it is. Or as much of what it is as I can discern. If anyone who has read this far does not deserve a medal, they at least deserve a campaign ribbon. Well done. I am sure I have become fixated on this matter but not in a way that is driving me mad—in a way that has drawn me in and fascinated me. I would like to think I could assist in the process of achieving just a little more certainty and clarification of the finer details of the final days of these eight brave men from Pudu. However, the essential truth of this story is not that something is wrong somewhere but that many details are wrong in many places. Eliminating all ambiguity may be too much to hope for but, where clarity can be provided, it should be and if any reader can assist to that end, I would appreciate hearing from them. Let’s hope history has not yet closed finally this chapter of her endlessly intriguing tale.

Chris Murphy

June 2022

REFERENCES

2/19 Battalion A.I.F. Association; R.W. Newton, (ed.). ‘The Grim Glory of the 2/19th Battalion’. 2/19 Battalion A.I.F. Association, Crows Nest, Sydney, 3rd Edition, 2006.

AWM. Report of Maj. R Steele, WO W. Wallace Sgt R.J. Kennedy. AWM226 9/2, Available at: https://www.awm.gov.au/collection/C2722197

Braddon, Russell. ‘The Naked Island.’ Doubleday and Company, New York, 1953.

Brune, Peter. ‘Descent into Hell: the Fall of Singapore―Pudu and Changi―the Thai-Burma Railway.’ Allen and Unwin, Crows Nest, NSW, 2014.

Chapman, F. Spencer. ‘The Jungle is Neutral.’ Chatto and Windus, London, 1950. Available at: https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.14185/page/n29

The Commonweath War Graves Commission website. Available at: https://www.cwgc.org/

Drummond, Alexander Hatton. ‘Papers, 1941-2001 [manuscript] Alexander Hatton Drummond 1911-1983’. State Library of Victoria: MS 13716.

The Defence Honours and Awards Tribunal. ‘Report of the Inquiry into Recognition for Far East Prisoners of War Who Were Killed While Escaping or Following Recapture.’ 2017.

Available at: https://defence-honours-tribunal.gov.au/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/FEPOW-II-Inquiry-Report.pdf

Edwards, Charles. ‘Life in Pudu After the Escape.’ pp.5-7. ‘Apa Khabar: The Newsletter of the Malayan Volunteers Group’. Edition 32, October 2012. Available at:

https://www.malayanvolunteersgroup.org.uk/uploads/1/0/7/3/107387685/mvg_newsletter_edition_32.pdf

The Find My Past website. Available at: https://www.findmypast.co.uk/

Garden R.J.P. ‘Survival in Malaya: January to October 1942.’ Self-published, New Zealand, 1992.

Harrison, Kenneth. ‘The Brave Japanese’. Rigby Ltd, Sydney, 1966. Available at: http://guyharrison.squarespace.com/bravejapanese/

Hembry Boris. ‘Malayan Spymaster: Memoirs of a Rubber Planter, Bandit Fighter and Spy.’ Monsoon Books, Singapore, 2011.

McCormick, Audrey Holmes, ‘Pat Garden and the Pudu Executions.’ pp.9-11. ‘Apa Khabar: The Newsletter of the Malayan Volunteers Group’. Edition 29, January 2012. Available at: https://www.malayanvolunteersgroup.org.uk/uploads/1/0/7/3/107387685/mvg_newsletter_edition_29.pdf

Meale, Katie Lisa. ‘Leadership of Australian POWs in the Second World War’. Doctoral Thesis, University of Wollongong, 2015. Available at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/4620

Nelson, Hank. ‘P.O.W. Prisoners of War: Australians Under Nippon.’ Australian Broadcasting Commission, Sydney, 1985.

Silver, Lynette Ramsay. ‘The Bridge at Parit Sulong: An Investigation of Mass Murder. Malaya 1942.’ The Watermark Press, Sydney, 2004.

Snelling, Steve. ‘Far East Escape.’ May 2013. Available at:

https://www.docdroid.net/SszyKPm/far-east-escapebritain-at-war-073-2013-05-pdf