What Great Leadership Looks Like

In his seminal work on the Railway experience, Peter Brune quotes Malay Volunteer, Pte Charles Letts, saying the private soldier’s experience as a POW “all depend[s] on your shoko” and shoko is Japanese for officer but Letts was not referring to Japanese officers; as he saw it, one’s fate as a prisoner was determined by the performance and character of the officers in one’s own army. Sgt Stan Arneil of the 2/30th Bn was someone who was generally supportive of the system. In the postwar years he wrote a highly partisan and loyal biography of his battalion CO, the controversial and divisive, Lt-Col. Frederick ‘Black Jack’ Galleghan. Yet even Arneil felt the need to excuse some of his more intemperate comments on the officer class made in his diary-based memoir, ‘One Man’s War.’

“Here and there in the book the reader will find criticism of the officers and this follows an army pattern which began before Hannibal fought in the Punic Wars. The lower ranks of all armies regard it as a right to criticise officers and nothing will ever change that. In fact our officers were a fine group of men, acting under orders at all times.”

That being said, readers of this webpage will know very well that while they were POWs, officers were not required to work and that some officers who were otherwise inactive and markedly reluctant to oppose the Japanese were galvanised into resolute action when the question of them working was raised. Paradoxically, in spite of their non-working status, the Japanese paid the officers considerably more than the men. Whereas an enlisted man received 10c or tuppence a day when working, officers’ pay ranged from $1 per day for lieutenants to $7 a day for lieutenant-colonels. ‘Weary’ Dunlop, who fought tenaciously against this level of privilege from the time he was in Java, encountered fierce opposition and was branded a ‘communist’ by his outraged brother officers when he sought to tithe their pay. On the Railway at Hintok Mountain he encountered Singapore Volunteer, Lt-Col. T.H. Newey; Newey was troubled by the money he was receiving—not because he was receiving too much or the enlisted men were receiving too little but because he wasn’t sure how he was going to spend it when he got home. ‘Weary’s’ icy suggestion was, “Ever think of buying a few lives?” Death stalked that camp like an old hag’s familiar and yet another officer in the same location was busy playing bridge all day and saving his pay to make a down-payment on a car. A third officer from the Suffolks who came through in April 1943 spent his time collecting orchids and hunting butterflies.

Such stories run contrary to the accepted view of military leadership insofar as officers are extended privileges so they can better perform their duties and the highest of all their duties is to attend to the welfare of their men. The occasions when this was not done were sufficiently frequent that one is led to conclude selfless leadership was more the exception than the rule. There is a substantial body of evidence maintaining a different view and portraying the officers as sharing the difficulties and travails of the men but, frankly, that is just so much bosh and is typically a feature of memoirs written by officers or biographies of officers, particularly those on the Line. It is also my view that the bulk of the memoirs about the POW experience were written by officers. As former Pacific GI, James Jones, author of ‘From Here to Eternity’ and ‘The Thin Red Line’ has said, most war history is, “written by the upper classes for the upper classes”. Most theoreticians and analysts, he added, give “little more than lip-service to the viewpoint of the … soldier.” To some extent, this makes sense since these are members of the literate classes writing for a literate audience but that must be understood by all who peruse these materials since it skews the narrative and over-emphasises a minority perspective; in so doing it runs the risk of drowning out the real story of the Burma-Thailand Railway and other POW locations which was that of the man on the ground, that very individual Jones so memorably labelled the “hairy, swiftly aging, fighting lower class soldier”.

As a case in point, it is strikingly difficult to find amongst the official records mortality rates on the Burma-Thailand Railway for officers as opposed to enlisted men. It is not that these figures would not have been known or could not have been—and probably were—readily calculated; it is more that they were air-brushed from the record and it is my contention that was done because they were an embarrassment to the officer class insofar as they exposed the level of privilege that existed and the falsehood of the myth that all officers shared the burdens and the risks experienced by their men. Nevertheless, we can make some detailed deductions from the numbers that are available. The following table shows the death rates for the most numerous Railway forces involving Australians. It should be noted that these are overall rates and include those of all officers and ORs who died.

LOSSES AMONGST AUSTRALIAN PARTIES ON THE RAILWAY

Arrival on Railway | Total No. Australians | Losses | Rate of Loss | |

‘A’ Force | 2nd October 1942 | 4,851 | 771 | 15.8% |

Dunlop Force | 25th January 1943 | 1,788 | 200 | 12.0% |

‘D’ Force | 23rd March 1943 | 2,242 | 400 | 18.0% |

‘F’ Force | 27th April 1943 | 3,662 | 1,068 | 28.9% |

‘H’ Force | 14th May 1943 | 600 | 179 | 29.8% |

OVERALL: | 12,255 | 2,518 | 20.5% | |

In the case of ‘H’ Force, the death rate amongst officers was 6 percent compared to over 30 percent for ORs. In ‘F’ Force only three officers succumbed whereas the number for ORs was 1,065. Of the 39 officers from the 2/30th Bn who were on the Railway, not one died. Sparrow Force went into captivity on Timor, was sent to Java and then the Railway; of their 48 officers, only one died while incarcerated and he drowned in September 1944—probably as the result of a US submarine attack. Of Reg Newton’s 2/19th Bn, four officers died while prisoners of war, none died on the Railway and all who did die, died in 1945. By contrast, 311 ORs from that battalion died while POWs. The death rate amongst Japanese guards and engineers working on the Railway was seven percent, a figure which led Dr Hank Nelson to make the confronting observation: “It may be that the Japanese were more likely to die on the railway than Australian officers.”

One of the most notorious of the Australian officers was the commander of ‘F’ Force, Lt-Col. C.H. ‘Gus’ Kappe [pronounced ‘Kappy’] who was regarded with such contempt by his men that they referred to him as ‘Kappe-yama’ or ‘the White Jap’. The Railway losses amongst ‘F’ Force were only exceeded by those of ‘H’ Force but, in Australian terms, ‘F’ Force was six times more numerous. For many of the postwar years, outside the inner circle, the references to Kappe’s performance were veiled. However, in 2013 at an ANU conference ABC broadcaster and researcher, Tim Bowden, spoke frankly in a public forum for one of the first times. The POWs themselves were too much the captives of old world values to name names but these days we are less restrained by such compunctions.

At the dreadful camp of Shimo (Lower) Songkurai, Kappe was rated “Jap Happy”, a term reserved for those leaders too timid after a face-slapping or two to oppose their captors. It was here that Kappe told men of the rank and file to stay away from him because he didn’t want to pick up their germs. Lt Ron Eaton remembers him at Kami (Upper) Songkurai being “completely non-active” and incompetent. When he spoke to Tim Bowden in 1982, Sgt Don Moore was still bitter that Kappe lent money to men on condition it was repaid at three times the price in English currency after liberation. This money had come from the proceeds of the camp’s canteen and Moore described it as “private enterprise purely and simply for himself”; others might refer to it as usury and others again could use the word extortion. Notwithstanding, officialdom saw fit to promote Kappe to brigadier during his captivity and, in 1946, to add insult to injury, award him an OBE “in recognition of his war service”. That really stuck in the craw of many ‘F’ Force survivors. It should come as no surprise then that, during his lifetime—which extended to 1967—Kappe never attended any POW reunions. Had he done so, veterans predicted they would have descended into hate sessions pure and simple.

There is a story of Lt-Col. Gus Kappe that simply must be told because it says so much of the good and the bad to be found in humanity. It comes from December 1943 when Kappe was put in charge of a group of prisoners being sent from the Railway to Saigon. At Bangkok the men boarded a barge and Kappe ordered his cases to be loaded while he met with the Japanese. In his absence, the men rifled through his stuff and removed cartons of Virginia cigarettes, tinned fish and other cans of food. Peter Brune’s masterful version of the story is based primarily on the recount of Sgt Keith ‘Curly’ Meakin from Kappe’s 8 Corps Sigs who recalled that once the vessel was underway:

“Lt.Col. Kappe ordered officers to conduct a thorough search for [the contents of] his boxes—nothing was found. He ordered a parade and criticised the men for stealing the food. There are many versions of what he was reported to have said, the most common account was that he stood up on the bridge, took off his shirt (displaying his good healthy condition) and offered to fight the culprits. He was jeered and ‘booed’ by the men who, by this time, were all smoking the Virginia cigarettes and the aroma was wafting past Kappe as he said, ‘You fools! It was your money I used to purchase that food for you to have on the voyage back to Singapore!’ and he was given more boos.”

So Kappe was certainly ineffective but he was not alone. Other officers did not contribute for a variety of reasons. Some were incapacitated to one degree or another and Maj. Noel Johnston, also of ‘F’ Force, is one whose health collapsed under the pressure. Lt-Col. S.A.F. Pond is one about whom the jury is still out but then that seems to apply to a great many POW leaders – even the good ones – and, in Pond’s case, it should be stated that his supporters made a good case. Identifying other ineffectual officers is more problematic and while I think I could narrow the field down in certain cases, I am also conscious that the evidence must be solid before such accusations are bandied about. So let us therefore confine the next part of this discussion to an officer at Hintok who will be referred to as Maj. X. Pte George Shelly of the 2/20th Bn was sent to the Railway with ‘U’ Battalion and he remembered this officer being:

“scared of his own skin, but sadly in charge of a lot of men. At the morning tenko the men would line up to go to work and he’d say, ‘Produce the bodies.’ He was bastard enough to make the men bring out the bodies of those who had died overnight in the huts, just so the Japs had a full count. It didn’t matter to him that near-dead men had to do that soulless thing.”

Strangely enough, Maj. X was another officer who never attended postwar reunions.

Unless I am sorely mistaken, this was the same officer featured in an anecdote told by Sgt Harry Holden (See note at end of article). The body weight of the men was down to about seven stone (or 44kg) and they were ordered to carry 100lb bags of rice, two men to a bag. The work was absolutely exhausting and, on one occasion, two of the lads dumped their bag in the bushes.

“The Jap guard at the rear of the strung-out column found it, there was a terrific roar. Back at camp the Japs turned on the tantrums and a muster was ordered. A well-fed officer exhorted the two culprits to step forward – ‘otherwise I will get a bashing’. There was a panic in his voice – nobody stepped forward. The man’s hour had come, here was his test and also his opportunity. His voice shrill with fear, he said ‘Will any two men come forward and take the blame?’ – there was stunned silence. Then an O.R. in the front rank said ‘I’ll be one if you’ll be the other’ – but the officer was not interested.”

Circumstances lead me to conclude that at Hintok it was this same so-called leader who berated the ORs for coming late to parade. He told them they would be marked AWOL and docked a day’s pay. This came as close as just about anything to causing an open rebellion from the ranks. The HMAS Perth’s PO Ray Parkin described the calls from the men as “self-righteous indignation.” The men’s protest actually produced an improvement in the rice ration and caused Maj. X to go out to the worksite the following day. When he arrived the ORs:

“told him to clear off back to camp, but he refused. In the end he hopped in to help the lads get finished. It may not sound much, but this was the man, I am told, who had no courage in action, and little moral courage at other times. The talk tonight is not of rights and wrongs—but of this man.”

Pte J.S. ‘Snow’ Peat of the 2/18th Bn noted that a number of officers would get “a bloody hiding” and not come back for the next one. Officers, he said, “were right out of the firing line” and some, when threatened, “Cringed like a mongrel dog.” But Sgt Don Moore of the 2/4th Anti-Tank Reg remembered one officer who was dedicated to duty and, in his own way, showed great leadership. This officer

“did have moral fibre. But he visibly shook when nervous: and he still did his job. Sometimes he was ineffectual; sometimes he made it. I remember him physically putting himself between the Japanese and some of the boys, realising that he could probably have stayed aloof. But he got into that situation, which meant he copped it. He would be visibly shaking; but he did it.”

Reg Newton consistently maintained that the Japanese despised non-working officers and referred to them as “drones”. The full officer complement he could have taken to the Railway with ‘U’ Battalion was 35 but he chose to limit this number to nine including himself.

In 1945 the Japanese concentrated officers in a camp at Kanchanaburi near the start of the Line. There were over 3,000 prisoners in the camp with the vast majority being British, Australian, Dutch and American officers; only 180 of this number were ORs but then someone had to do the work. For a period the camp was administered through a “command committee” but that didn’t work and it frustrated the hell out of the Japanese so they simply put Royal Artillery officer, Lt-Col. Philip Toosey, in command despite his lack of seniority with the result that:

“Toosey felt more caged in and more miserable than at any time since becoming a prisoner. He was surrounded by senior officers who were more concerned with jostling for authority and saving themselves than they were for the welfare of the camp. He hated his role there. … He mused on this in 1974 …. ‘The officers were much more difficult than the men.’”

If Toosey were an apiarist, he’d have experienced a serious shortage of honey in his time at Kanchanaburi. But no one for a moment should suggest that the role of the officers in captivity was easy. The ORs were a tough audience and set standards for others which were sometimes higher than the ones they applied to themselves. In the early period after the capitulation in Singapore there was a great deal of hostility and resentment. The men felt let down by their leaders and were highly resistant to authority. Things improved as men saw the need for leadership and control in dealing with a common enemy but a level of truculence remained. Lt Basil Billett of the 2/40th Bn remembered that:

“When you came on parade you had to stand up, and as far as the Japs were concerned you stood up. Sometimes you’d be on parade for some time, waiting, before the Japs did the count, and sometimes blokes would sit down. Sure, they had beri-beri and burning feet and they were weak but they placed me in a very embarrassing position. You’d be running a risk all the time. On one occasion when I said to these blokes, ‘You know if the Jap catches you sitting down it won’t be just you getting a bashing, but I’ll get one too. You know that.’ The response was, ‘Ah, she’ll be right.’ And there was nothing you could do about it. Naturally enough, they were going to get caught sooner or later, and when they did they were given a lift under the ear, but I was taken up to the guard room and I was there for half an hour being cross-questioned and yelled at and told not to let it happen again. When I got back to camp it’d be, ‘How did you get on?’ And I’d reply, ‘How did you expect me to get on? You don’t give a bloke much of a go, do you?’ Then they’d say, ‘Well, that’s what you bloody-well get paid for, anyway’. You didn’t get any sympathy. Unless you got cooperation from these blokes it was a very embarrassing position to be in charge. And of course if you tried to do anything with them you’d be the worst bloke in the world. You were the boss and yet you weren’t the boss.”

But at Bicycle Camp in Java Cpl Doug Hawkes of the 2/40th Bn was amazed at “how stupid some of our people could be”.

“This smart alec Australian annoyed a Japanese guard by continually flicking pebbles towards him until the guard had all the prisoners called out of their two huts in that part of the camp. We had to stand to attention in front of the guardhouse while the Japs tried to get the culprit to confess. Then they went along the line, bashing a few, and staring closely at each person. If you as much as blinked they took you out into another group for punishment. When the guard stared at me I had enough presence of mind to stare straight back over his head and not move a muscle. But my mate, poor old Frank Bassett, was one they picked out and gave a good bashing [to]. The bloke who caused that was one of those types who always criticised others as silly buggers if they got caught out by the Japs, and yet he would do something irresponsible and let everyone else pay the penalty. There was a bit of ill-feeling towards him for quite a while, but we had these sort of blokes everywhere.”

At Kinsayok on the Railway during the monsoon period when the number of deaths from cholera and dysentery mounted and Japanese demands associated with their ‘speedo’ increased, the POWs felt themselves on the brink of a precipice and reckoned they couldn’t take any more. Pte Jack White of the 2/40th Bn remembered men thinking the Japanese had “just about overstepped the mark.”

“[T]hings got that tough that one day we knocked the heads off our pick handles and were ready to go for them. Ron Williams was there on the job and he calmed things down. He said, ‘We’ll weather it a bit longer’, and talked us out of it.”

This was only one of many moments when Lt Ron Williams of the 2/40th Bn stood up and he proved to be one of the exceptional POW leaders both on the Railway and in Japan. Leaders like him saved the lives of many.

By contrast to Lt-Col. Gus Kappe’s reluctance to have men come near him at Shimo Songkurai, at Taunzan on the northern end of the line, Dr Rowley Richards of the 2/15th Fld Reg. was fighting hard to reduce the ravages of cholera. Treatment would not have been possible without the selfless dedication of the medical orderlies whose chances of contracting the contagious bacterium were high indeed. So, to limit the spread, Richards declared the cholera tent off-limits to all but him and the orderlies who volunteered to stay with the sick.

“But the young doctor would turn a blind eye when he saw one of two figures creeping on their bellies through the long grass towards the isolation unit. He knew who the furtive figures were: Padre [H.A.] Smith [of the 2/19th Fld Ambulance] or [Lt-]Colonel [J.M.] Williams, [of the 2/2nd Pioneers] going through to share hope and companionship with the dying men.”

It would be hard to argue that that was not great leadership.

In relation to Reg Newton, one of the men at Pudu, Pte Alex Drummond of the 2/29th Bn, referred to him as ‘Nazi Ned’ and had a particularly sharp clash with him during an orderly room hearing in May 1942. Drummond who was something of a self-appointed spokesman for the barrack-room malcontents and had strong communist affiliations was motivated to stir up one of the ineffectual and naïve officers in an attempt to usurp Newton’s authority. According to Drummond, there were times in Pudu when Newton was jeered and booed by the men. After the war this same individual set up an organisation called the 8th Division Old Comrades’ Association from which all officers were excluded. However, even Drummond on the Railway came to the reluctant and grudging realisation that ‘Roaring Reggie’ was not all bad. At that time Drummond was a member of the ill-fated ‘H’ Force where he got to see dysfunctional leadership up close and personal. When he encountered members of ‘U’ Battalion in the middle of the worst period when speedo, monsoon and cholera combined to make the bad conditions simply awful, he was surprised by the good shape of Newton’s men: “they all look well, their Officers have got a bit of guts [and] when one of the boys were bashed they jacked up & the Officers threatened the Japs that they would march the men out of the cutting if it happened again.” Attributing any credit to Newton for this situation was a step Drummond’s pride prevented him from making but these comments coming as they do from such a strident and unreformed critic, were high praise indeed. They reinforce the ancient wisdom that it is easier to be an Indian than a chief.

More sensible and measured comments were made by Pte George Shelly of the 2/20th Bn who told Pattie Wright:

“Our lot got to a few camps on the Line over about fourteen months. I was in U Battalion which had ‘Roaring’ Reg Newton as the commander. We were lucky as we had a structure and officers who would stand up for us when it was needed, and consequently we didn’t have heavy losses. Not that we didn’t work like navvies and come into contact with cholera and every other thing that the Japanese and the Line could throw at us….”

As for how the men would have got on without clear leadership and direction, comments in the preface to the Prisoner of War section of the 2/19th’s history are pertinent. In describing what it took to survive captivity, it is noted that, unlike the 270,000 Asian labourers shanghaied by the IJA to build the Burma-Thailand Railway, POWs did not have to face their difficulties alone: “generally everyone was working for the well-being of all others of the Unit or party.” This helped with the organisation and enforcement of regimes such as the careful and orderly distribution of their meagre rations as well as “strict hygiene measures” which required a great deal “more work, effort and hardship for some” but were ultimately to be of benefit to all. The sense that the men were a cohesive unit allowed them to take delight in any small victory over their captors and this was felt to be something which strengthened the will to live and to help one’s mates. Of the 270,000 Asian labourers, it is estimated 90,000 died although the actual number could be higher. Most of those 90,000 died lonely, anonymous and ignominious deaths and all of them were sacrificed on the altar of the IJA’s demented drive to meet deadlines, “follow orders” and build an empire.

The harsh reality is that the natural state of man is not characterised by harmony, kindliness and co-operation. The evolutionary origins of the savage beast at humanity’s core date back several hundred thousand years whereas civilisation’s restraints on natural urges date back several thousand. The Burma-Thailand Railway was rather like Conrad’s Congo which later became Francis Ford Coppola’s Mekong: the further upstream one went, the closer one came to the dark heart of man. As one survivor put it, up-river men “lived by the law of the jungle, ‘red in tooth and claw’.” While the myths talk of egalitarianism, selflessness and sharing, one sees occasional glimpses behind the veil suggesting that things were not always the way survivors portrayed them in later years. According to Pte Keith Memory Firth of the 2/40th Bn:

“mateship was something very valuable, unfortunately, and I suppose we were all guilty of it, quite often it was every man for himself. When you get down to a pretty low ebb and it’s your own self you’re trying to save, you’ll give yourself a bit of preferential treatment even if it’s unfortunately at someone else’s expense.”

This is honesty that is rare but no one should blame men for such conduct. For me, this is where the drowning man analogy comes in: Is it selfish to save yourself when you cannot physically support a drowning man any longer?

It is interesting that the man who in his student days was passionately anti-communist, ‘Weary’ Dunlop, was accused of being a communist when he showed strong leadership and compassion by tithing the officers’ salaries in Java. Yet in Japan the Americans were accused of allowing free enterprise to run wild. Here again life was lived by tooth and claw under the guise of a trading system so unregulated by camp officers that the rampant deal-making affected men’s chances of survival. Pte Bill Cameron of the 2/40th Bn wrote that in the Omuta camp which housed 1,700 POWs, three or four American ORs controlled everything through unfettered bully-boy tactics.

At Fukuoka Dvr David Runge of the 8th Div AASC said men would sell the bird in their hand for two in the bush. A man might call out, “I’ve got rice now for rice and soup on Wednesday night” and a hungry man would accept the deal. The problem was, “When Wednesday night came he’d find he owed about six rations and he couldn’t pay them. After a while they’d declare him bankrupt. Nobody would trade with him.” And that might have been fine if it were left at that, but clearly it wasn’t. Men who owed debts and looked like skeletons would find “as soon as they came through the chow line with their rice and soup there’d be blokes there that they owed the food to and they would take it off them. They wouldn’t get anything to eat.” One imagines these so-called comrades collecting such debts did not say ‘please’ or ‘thank-you’. It got so bad that the Dutch padre had to intervene and protect the bankrupts who would sit in one place where he could supervise the repayment of their debts in a regulated fashion: giving away a maximum of one meal per day and eating the other two themselves.

Times were desperate and conditions were dire. So it was in these circumstances that strong leadership was needed more than ever and it was not of the kind we demand in our comfortable 21st Century existence. POWs could not afford the luxury of horizontal structures and collaborative procedures with teams workshopping agreed outcomes to ensure uptake and ownership of the process. They could not facilitate a ‘conversation’ or focus on ‘buy-in’. When talk was required, it had to be one-way and, surprisingly, that runs counter to military orthodoxy, particularly in the small-teams environment, where leaders are encouraged to talk to men as equals and share what they know so all members are on the same page.

Those who were POWs of the Japanese in the Second World War were faced by something unprecedented. Compare the earlier anecdote of ranker truculence told by Lt Basil Billett with the actions of two officers from the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders at Pudu Prison in 1942. When they arrived at that jail relatively late in the piece, they found the tough fighting men of their battalion had become a law unto themselves and were not taking direction from anyone. These two resolute individuals, Capt. David Boyle and Lt Ian Primrose, decided to do something about it and ordered a parade. When the RSM called them out, some men simply lay on the ground to express their complete contempt for authority. This did not impress Boyle and Primrose who:

“just waded into the figures on the ground with boots and fists and kicked and hit every man who was not rigid at attention in the ranks. It all created quite a stir, not the least among the Japanese. Captain Boyle then went on to say how proud he was of his Unit and he was going to make sure that nobody disgraced the Regiment from now on. It was the most amazing reversal of conduct you could imagine.”

It is my view that witnessing this incident was a watershed moment for Reg Newton and was instrumental in making him the exceptional POW leader he became. He realised that stern measures would be required at critical times and also that physical force would be needed to reinforce the message with reluctant and recalcitrant individuals. Newton was not the only one to go down that path; that Briton referred to earlier, Lt-Col. Philip Toosey, issued strong corporal punishment on occasions. On the island of Hainan where dysfunction reigned, men set up a vigilante group with drum-head courts martial and severe beatings as punishments. Author Roger Maynard comments that “While the method was controversial … the result was to restore order in a community whose lives were being threatened by the actions of a few.” On the Railway, that exceptional Australian medico, Maj. Bruce Hunt, used force when he deemed it necessary to protect the greater good.

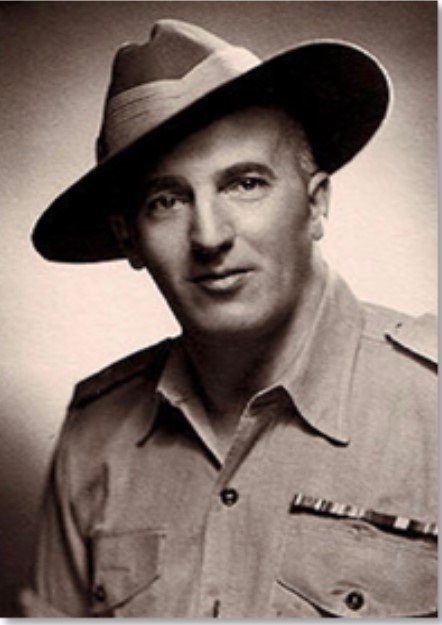

Maj. Bruce Atlee Hunt, Hero of ‘F’ Force.

SOURCE: 2/4th MG Bn Assoc. Website.

In fact, it is worth spending a few moments on the subject of Maj. Bruce Hunt. The members of ‘F’ Force were lucky to have a figure strong enough to step into the void created by the incompetence and inability of their formal leaders. In May 1943 when things were darkest at Shimo Songkurai, Hunt called the men together and made an impassioned appeal intended to snap them out of their lethargy and despondence. When one man was caught stealing food, Hunt told him to step outside. The unabashed culprit threatened the doctor saying, “I’ll bloody well eat you.” But he under-estimated his adversary and Hunt “gave him the most terrible physical hiding”. Lt Norm ‘Killer’ Couch of the 2/20th Bn commented:

“Hunt regarded maintenance of morale as an instrument of survival: ‘When thieving threatened discipline, Major Hunt restored control with one application of corporal punishment. In retrospect, the uninformed may deplore this courageous and desperate action. The perilous conditions demanded drastic action.’

In his memoir Cpl James Boyle of the 2/4th Motor Res. Transport Coy strongly repudiated subsequent criticisms of these actions made by officers in Changi. Such actions were necessary, Boyle said, and “no one apart from those who helped to build the Burma railway was in any position to pass judgement.” Boyle went on to describe Hunt as “a man in a million”. Lt Norm Couch said, “No verbal skills can create a fitting profile of a mighty man such as Bruce Hunt, Major, A.A.M.C., 8 Div. A.I.F. Bruce Atlee Hunt surmounted apparently impossible obstacles, in an environment which now defies even the imagination of witnesses to these events.” Lt Bob Kelsey of the 2/26th Bn was so impressed with Hunt’s work at Shimo Songkurai he wrote: “To this camp God sent Bruce Hunt.” He went on to highlight one memory from the scores he had of “this remarkable man”:

“It is a picture of him visiting the sick, himself exhausted and recently beaten, and pausing to place a hand gently on a feverish forehead, and murmuring in his beautiful accent, ‘Poor old boy’. God rest his soul.”

If that is not great leadership, I will never know what is.

So while officers in captivity were criticised and while a lot did not perform as they should have, there were others who stood up and distinguished themselves with their efficiency, their bravery and their selflessness. Sure, there was a degree of residual bitterness amongst survivors from the other ranks that outlasted liberation and, in many cases, remained unreconciled even unto their dying days. However, on this as on other matters, opinions differed and while it would be fine for we latterday observers to suggest veterans should have forgiven and moved on, that was by no means an option for many nor a panacea for all. Still, it worked for some and, when achieved, this generosity of spirit was truly admirable. In 2007 WO2 Bert Mettam of the 2/29th Bn, told Pattie Wright “no man knows what he might do when he is put to task in such an unspeakable place as that railway, or put under the enormous pressure of keeping men alive for so long when it’s almost impossible.” The veteran quoted earlier, Pte Keith Memory Firth, also expressed it beautifully when he said of ineffective officers, “I never held it against them.” Not only are those great-hearted acknowledgements of the difficulties faced by others but they are wonderful instances of survivors who realised life involves issues bigger than their personal self-interest and were able to make peace with that.

What a model for the rest of us and, like the examples of selfless and courageous leadership, they are inspiring examples of what at our best we can be.

Chris Murphy

May 2022.

NOTE REGARDING ‘HARRY’ HOLDEN

The anecdote from Sgt ‘Harry’ Holden is re-told in the Don Wall book, ‘Singapore and Beyond’ and the individual concerned could be one of two members of ‘H’ Force: NX65437 Sgt George Henry Holden, RAA HQ 8th Div., or NX37424 Sgt Henry John Holden, 2/30th Bn. Both survived the Railway and the war. If any reader has more definitive information, I would welcome hearing from them but in the meantime, after quite a lot of searching, unfortunately, that is as definitive as I can be.

REFERENCES

2/19 Battalion A.I.F. Association; R.W. Newton (ed.). ‘The Grim Glory of the 2/19th Battalion’. (2006.) pp. 322, 476 & 528.

2/19th Battalion Nominal Roll. (Website.)

Stan Arneil. ‘One Man’s War.’ (1980.) p.3.

AWM Encyclopedia POW page. (Website.)

Tim Bowden. ‘I Don’t Think I Deserve A Pension.’ (2013.) p.45.

James Boyle. ‘Railroad to Burma.’ (1990.) p.135.

Peter Brune. ‘Descent into Hell. (2014.) pp.494 & 697.

Alex Hatton Drummond. ‘Papers. 1941-2001.’ [n.d.] p.238.

Edward E. Dunlop. ‘The War Diaries of Weary Dunlop.’ (1986) p.258.

Cameron Forbes. ‘Hellfire.’ (2005.) p.317.

Peter Henning. ‘Doomed Battalion.’ (1995.) pp.182-3, 216, 291-2 & 306.

Robert Holman and Peter Thomson. ‘On Paths of Ash’. (2009.) pp.252-3.

James Jones. ‘WWII: A Chronicle of Soldiering.’ (2014.) p.24.

Roger Maynard. ‘Ambon.’ (2014.) pp.192-3.

Gavin McCormack and Hank Nelson (Ed.) ‘The Burma-Thailand Railway: memory and history’. (1993.) p.19.

Reg Newton. ‘Transcript of Interview with Members of the Gaden Family.’ (1992.) Website.)

Ray Parkin. ‘Into the Smother. (2003.) p.438.

Julie Summers. ‘The Colonel of Tamarkan.’ (2005.) pp.260 & 268-9.

A.J. Sweeting. Part III: Prisoners of the Japanese. in Wigmore’s. ‘The Japanese Thrust.’ (1957.) p.571.

Don Wall. ‘Singapore and Beyond.’(1985.) pp.191-2.

Pattie Wright. ‘The Men of the Line.’ (2008.) p.15. pp.177-9.