THE BOOK AND FILM VERSIONS OF

‘THE BRIDGE ON THE RIVER KWAI’

INTRODUCTION

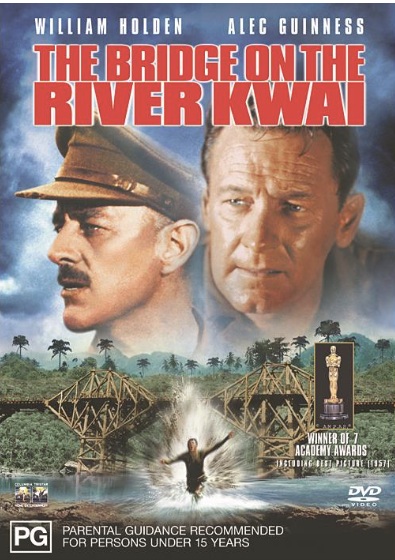

For many people, especially those of my vintage, David Lean’s classic 1957 film, ‘The Bridge on the River Kwai’, was their first introduction to the story of the Burma-Thailand Railway and is certainly the best-remembered and most celebrated depiction of captivity in Japanese hands during the Pacific War. This is even moreso with British audiences because, for them, the FEPOWs’ story seems to have been less central than it was to this country’s retelling and recollection of World War II experiences; the reason is probably because, as historian R.P.W. Havers points out, “half of the Australians who died in the war against Japan died as prisoners”. For the British, the FEPOW chapter was one of many stories they could have told and also not one of its most glorious; concomitantly, it is notable how many British books about the Railway begin with some reference to Lean’s 1957 film, which represents a contextualising unnecessary in this country due to the greater public awareness of the history of captivity in Japanese hands.

Of course, David Lean’s 1957 film was based on Pierre Boulle’s 1952 novel of the same name. Many will know of the literary licence taken in the film’s deviation from historical fact but fewer will know of the film’s deviations from Boulle’s novel. In this article, I intend to examine the tweaks made by David Lean and his team which took a good story and made it immeasurably better. But, be warned: if you have not read the book, this article, featuring spoilers galore, may very well destroy that experience for you. The most significant change to the novel made by the film was its ending so, if you would like to read the novel and enjoy it not knowing how its end differs from that in the film, leave this page now and return to it only when you have finished your homework and done all your chores.

For those who remain, in the article that follows, I will outline some of the well-known instances where the film deviated from fact before then outlining some of the areas in which the film deviated from Boulle’s novel. Finally, I will discuss ways I believe David Lean’s film improved on Boulle’s highly-engaging original material, taking a story which was very good and crafting from it a work of luminous brilliance.

Before I do any of that, I want to emphasise that the novel and the film are both works of fiction and this discussion proceeds on that basis. Prior to the film’s release in Australian cinemas, it caused a deal of controversy amongst former POWs, largely because of its portrayal of a British officer and his men constructing with great drive, determination and commitment, a high-quality bridge used to aid the Japanese campaign in Burma. The film was only allowed to be shown in Australian cinemas if a disclaimer authored by Lt-Col. Frederick ‘Black Jack’ Galleghan preceded it. The discussion here proceeds in a similar spirit insofar as we are dealing with fiction rather than fact and nothing said here should be taken to reflect on the real conditions experienced by POWs working on the Thai-Burma Railway. I should also add that the catalyst for this discussion was a considerable oversight on my part inasmuch as it took me a very long time to get around to reading Boulle’s novel. I thought I knew enough of the story to rely on the film’s depiction and some other authors’ comments on it. I was wrong and this article explains why.

The reconstructed steel and concrete bridge at Kanchanaburi, as it was in 2022.

This is the popular tourist destination billed as ‘the real bridge over the River Kwai’ but, as discerning tourists and pilgrims to the area know, that is not quite the full story.

AREAS WHERE THE FILM DEVIATED FROM FACT

It is well-known that David Lean and his team of cinematographers never set foot in Thailand or Burma and that the film’s outdoor scenes were shot entirely in Sri Lanka (or Ceylon as it was then known). It is also well-known that there was no bridge on the River Kwai. Although 688 bridges were constructed over the Railway’s 415km length, none of those crossed the river known as the Kwai Noi. The bridge at Kanchanaburi, which pilgrims and tourists such as myself visit in droves every year, was constructed over the Mae Kluang River and, in fact, at that location, there were originally two bridges side-by-side, a steel one and a wooden one; the wooden one is no longer there even though its original approaches remain as part of the JEATH War Museum (a photograph of which appears on this page of my website). Of course, a great many people know these two Kanchanaburi bridges are indeed on the River Kwai and they know that because they have been there and walked across the steel and concrete one but a lesser number will know that the watercourse which flows under it was not known by that name during World War II. Realising that the celebrated film had made their bridge a popular tourist attraction, in 1960 the canny councillors of Kanchanaburi renamed their section of the river, previously known as the Mae Kluang, to match the river depicted in the book and the film. While the former River Kwai had not been far away, it was on a different branch of the area’s ample waterways.

When construction of the steel and concrete bridge was completed in May 1943, the wooden bridge beside it was pulled down. The Japanese then reconstructed it in (I believe) late 1944 when Allied aircraft started systematic bombing of the steel bridge. The reason they reconstructed the wooden bridge was that it was easier and quicker to repair than the steel and concrete one.

The commando team headed by Jack Hawkins’ character in the film is designated Force 316 but no such force existed. However, there was a Force 136 and the novel’s author, Pierre Boulle, had been one of its members. (If anyone is interested, the best account I have read of this group’s exploits is in Boris Hembry’s memoir, ‘Malayan Spymaster’). As for the precise nature of Boulle’s work and role in Force 136, that is something about which I know almost nothing but is a topic which might merit further exploration.

However, it should be stated clearly that there never was a commando attack on any of the bridges along the Railway’s 415km course.

Furthermore, unlike William Holden, no POW ever successfully escaped from any Railway camp during the railroad’s construction. A few POWs escaped successfully from places like Ratburi or Ratchaburi (located between Bangkok and Ban Pong) but they did so late in the war when its outcome was clear to every Thai citizen and when Allied teams had been inserted near POW camps and were able to provide aid to guerrillas and the odd escapee. The best example of an escape in that category is described in Desmond Jackson’s memoir, ‘What Price Surrender?’ Another book which simply must be read in relation to the improbability of escape being successful in the area in which William Holden’s character operated is James Bradley’s classic, ‘Towards the Setting Sun.’

Both the film and the novel deviated from facts in ways so numerous that I would bore you witless if I listed all of them but a few which stand out are that the British unit building the famous bridge had remained together, up to that point, through all their captivity whereas, in reality, no POW railway entity was able to preserve its original structure; indeed, the Japanese quite deliberately broke up pre-existing structures and imposed their own, probably for logistical reasons but also to diminish the effects of their captives’ unit solidarity. As Boulle tells it, about five hundred POWs were employed building the bridge (“only a few miles from the Burmese border”, p.18) and its construction took six months but they arrived at the worksite about three weeks prior to 7 December 1942 (p.42). Those details are clearly fictional since the Japanese employed a great many more than five hundred POWs and romusha on bottle-neck projects represented by major cuttings, bridges and viaducts. Also, while the building of the two bridges at Kanchanaburi did take about six months, unlike the fictional bridge, which was completed just prior to the joining of the line’s two ends, the Kanchanaburi project finished five months before trains were able to run the full length of the line.

In both the film and the novel, the Alec Guiness character is a full colonel and his camp commandant, Col. Saito, is also a full colonel. Neither of those things could have happened in the real Railway because POW full colonels had been sent away with senior officers in about August 1942, some months before large parties of POWs were sent to work on the railroad’s construction. The exception was Brig. Arthur Varley who had been sent to Burma with ‘A’ Force in May 1942 and was re-assigned to Thanbyuzayat from Tavoy in October that year. Moreover, no Japanese full colonel was ever commandant of a camp containing 600 POWs. In fact, there were cases when lowly NCOs were in charge of 2,000 POWs and the highest-ranked camp commandants were usually lieutenants or captains and they could be in charge of large camps or whole complexes of camps. So, that might be nit-picking, and, while I could do a lot more, I think it is in the best interest of all that I move on rather than agonise over minutiae. After all, we are dealing here with fiction rather than fact and that must be the focus.

The front cover of Boulle’s 1952 book which went on to be published in many editions and several languages.

The most specific information I can find through Google on its sales is that it was a “multi-million copy” best-seller.

(This edition of the book clearly appeared after the film’s release since the bridge depicted is modelled on the one David Lean had built and blew up in Ceylon: By way of a quick check, see the film poster shown at the top of this page.)

AREAS WHERE THE FILM REMAINED FAITHFUL TO THE NOVEL

The first comment I would make in this section relates to a disclaimer that appears in the opening credits of the TV series ‘SAS: Rogue Heroes’. It begins with the common filmic claim, “Based on a true story” but then adds “Those events depicted which seem most unbelievable … are most true” and finishes with: “This is NOT a history lesson”. I think that is a useful reminder of an enduring principle: if entertainment were entirely true to history, it would not be anywhere near as entertaining. Of course, film-makers are notorious for giving a story which would have been captivating in close to its original form “the Hollywood treatment” and, in so doing, killing the goose that could have laid their golden egg. From my personal perspective, the Angelina Jolie film-version of Louis Zamperini’s experiences in ‘Unbroken’ is a prime illustration of the problem. So please let it be noted that I am not here criticising the film for being counter-factual; I am seeking mainly to comment on the deviations film-makers made from the novel on which it was based.

Something I found interesting is that Boulle’s novel was first published in 1952. By the time Boulle was writing his novel, a number of POW memoirs had already been published: as an example, my bibliography lists five. But the literature was nowhere near as extensive as it later became. That indicates to me that Boulle had a fair interest in and knowledge of this topic before he wrote his book. There are some surprisingly accurate comments and details in it—perhaps that was one of the reasons for its success: mixing a few lies with a fair bit of truth, or something closely approximating it. As a result, the film started with a solid foundation inasmuch as Boulle’s novel took a remarkable page from history and tweaked it to turn it successfully into escapist entertainment. The Alec Guinness character, Col. Nicholson, is based very closely on the novel’s depiction of him, as is that of Nicholson’s antagonist, Col. Saito. The film’s general plot follows closely that in the novel, notably in regard to the confinement of Nicholson to a punishment cell, Saito’s stress, self-doubt and alcoholism and even to the novel’s most preposterous premise and that was that a senior Japanese officer would ever allow a captive of whatever rank to take the kind of control the Nicholson-Guinness character did, depicted so effectively in the film and novel’s conference arranged at Nicholson’s request and illustrating Saito’s complete defeat in the face of Nicholson’s steadfast defiance.

Other elements of the film which are very close to the novel include the discussion at Calcutta about the risks associated with William Holden’s character doing parachute training. Oddly, in the novel Boulle has experts claiming it would take six months to train a man to parachute. I know for a fact that the Australian Army does it as a matter of course it in a fortnight and, for a special operation, I’d expect they could do it much more quickly than that. The angst experienced by the young Lt Joyce over the question of whether he would be able to use his double-edged Fairburn-Sykes dagger if the need arose, is also very true to the book. Another great element of Boulle’s original plot is the drop in the river’s water level on the night before the bridge is to be blown. Even the final discovery by Nicholson (Alec Guinness) of the explosive charges and the electric cord leading to the detonator is very true to the novel. These factors illustrate to me how clever Boulle’s original plot was. Whether I would have realised that without its dramatic realisation on the big-screen is something I can never answer because my reading of the book is now so indelibly ingrained with so many enduring and effective images and recollections from the film.

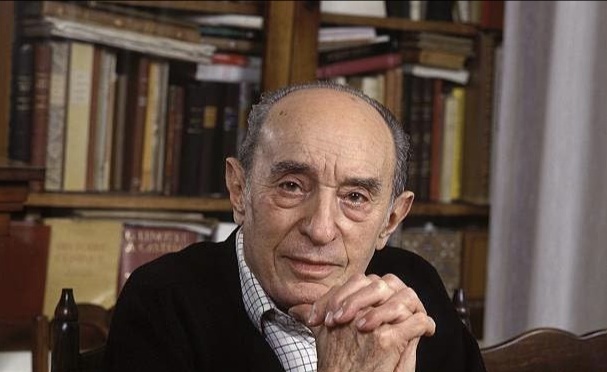

Author Pierre Boulle who went on to write ‘The Planet of the Apes’, indicating he was no slouch where writing hits was concerned.

Masterful British film director, David Lean, whose works included ‘Hobson’s Choice’, ‘Lawrence of Arabia’ and ‘Ryan’s Daughter’.

WAYS THE FILM IMPROVED ON THE NOVEL

I mentioned above that no POW escaped from a Burma-Thailand Railway camp as and when William Holden’s character did but I should also point out that there is no direct equivalent to the Holden character in the novel, even though his name, Shears, is the same as one member of the novel’s three-man Force 316 team. Still, the Holden character is a great invention. For one thing, he fills a gap in the novel in that he was able to give insights to the Force 316 team about what was going on in the POW camp (since they strenuously avoided any direct contact in the novel). No doubt Holden was included because his high-profile and fame would give the film more traction with US audiences—where the big money could be earnt. The Holden character’s womanising nature and his pretence that he was an officer are also great details added by the film-makers, particularly when one considers that wonderful scene where the Jack Hawkins character calls the Shears-Holden character out on the subject. As for Jack Hawkins’ character, he is an amalgam of the novel’s Col. Green and the insertion team’s “Number One”. That’s a change that also works well.

In the book, the Thai partisans who assist the Force 316 team are not all lithe and alluring 21-year-old virgins as depicted in the film and yet the film’s inclusion of that element is highly effective since it gave the film-makers a vehicle to include many enticing elements and create some clever sub-plots. This also means the book has no equivalent to the scene in which the Thai virgins bathe in the river in a semi-naked state and there is no equivalent of the Jack Hawkins character pursuing a renegade Japanese escapee and being wounded in the foot as a result. Perhaps this is included to show how tough and gritty the Hawkins character is or why, in the film’s climactic scene, he had to be stationed up on the high-point overlooking the river and bridge with the mortar rather than being down on the river with Joyce and the William Holden character.

Finally, the book’s climactic scene is very close to the way it was represented on-screen, even to a last-minute intervention in the physical fight between Nicholson and Joyce very close to that in the film involving William Holden’s character. In the novel, Joyce uses his knife on Col. Saito and then Nicholson struggles with Joyce. Warden (Jack Hawkins in the film) sees all this from the opposite bank and makes the decision to open up on the group with a mortar. As with the novel, the Hawkins character is the only Force 316 survivor of the action. However, the biggest and most surprising difference is that, in the book, the bridge is not destroyed. Boulle has a train set off charges which cause it to derail and fall into the river but the bridge remains intact—which is a rather unsatisfying end, especially since it is Warden (i.e., Jack Hawkins) who kills those remaining alive near the detonator on river bank.

The novel’s third-person narrative effectively stops at this point. For the last few pages it switches to Warden when he is back in Calcutta presenting his unvarnished version of the facts to his superior, separate from the official report which stated that the bridge remained intact “thanks to the British Colonel’s heroism”—and that is odd because, I don’t see why an official British report would celebrate the fact that a Japanese railway bridge was left intact after a raid by one of their own teams sent to destroy it succeeded only partially. I found that shift in the novel’s focus odd but then I had the disadvantage, when reading it, of knowing how this story was going to end—or at least thinking I did. And this is where the film’s most inspired change to Boulle’s story comes in and that is Alec Guinness’s Nicholson character being struck by the mortar fire, uttering that great line, “What have I done?” and then falling insensible on the detonator plunger so that the bridge explodes at the perfect moment while the train is on it. What a superlative example of masterful story-telling. It is one that provides the opportunity for that complex character played so effectively by Alec Guinness to die on-screen with great pathos in another tour de force from the memorable oeuvre of one of my all-time favourite film directors, David Lean, who was, at this time, at the top of his game but would go on to even more lyrical and sublime on-screen representations of the human condition.

Chris Murphy

April 2025