The Importance of Humour

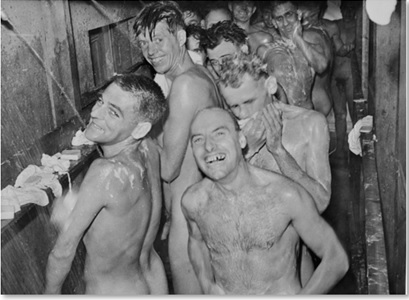

A wonderful depiction of group joy.

Prisoners showering after liberation in Yokohama, 1945.

SOURCE: AWM.

When the work on the Burma-Thailand Railway began winding down at the end of 1943, the Japanese started sending Allied prisoners of war back to concentration points around the Thai town of Kanchanaburi. Some of the men were so shattered from their ordeal that the spark of their being was all but extinguished and it was going to need extraordinary care to coax it back to life. Lt-Col. Philip Toosey, RA, was at Tamarkan when a group arrived from up-river.

“I remember one man who was so thin that he could be lifted easily on one arm. His hair was growing down his back and was full of maggots. His clothing consisted of a ragged pair of shorts soaked with dysentery excreta; he was lousy, and covered with flies all the time, which he was too weak to brush away from his face and his eyes and the sore places on his body.”

Scenes such as these remind us that life consists of the complex interplay of forces which act on our being like a gimbal. There are motivations and doubts, frustrations and desires, pleasures and disappointments. Mostly we are seeking to achieve a state of equanimity but pressures and pain can upset the balance. When the pressure is intense, we must look deep into our souls and there will come a time when we all will ask whether we can sustain it. “Pain is just weakness leaving the body.” That is a great line but glib. Still, it speaks to an essential truth which is that every human must find a way to deal with pain and, if they wish to live, to push through. It can be hard to push when every fibre and sinew of the body is crying against it. But it is by no means easy to stop either. Stopping is the finish line of the existential foot race. It is that last line that Hamlet in his famous soliloquy found so hard to cross. Stopping is easy but at the same time difficult. For him, as for many, it was the fear of letting go rather than the desire to keep a grip which sustained life. But when the travails of the present mount to such a degree that the path to the future cannot be seen, then we are more like Macbeth who viewed life as a trail across a vast wasteland leading the way to dusty death. And that is hardly life at all. It is existence, not much better than that of the primordial slime that emerged in the Proterozoic era.

On the Burma-Thailand Railway many POWs were motivated by hope and many were motivated by hate. Whichever applied, the key point is that they were motivated. That motivation was often the last ember of essence and there must have been times when only the faintest glimmer sustained their life-force like the final coal of a fire from the night before. A green twig or a dusting of rain might extinguish it entirely. But a little dry fuel and a helping hand could nurse it back to life in the morning.

The ability to stoically accept extraordinary misfortune is admirable but it cannot be achieved without an ongoing mental struggle; it is a war that is fought against thought, where the battleground is the mind and the enemy oneself. But stoicism is a burden that cannot be endlessly sustained and laughter on the Line often provided relief. A joke could break the tension and lighten the load. Of course, one would expect to see pleasure derived from concerts, songs and parodies performed in the face of adversity. One would expect it at times when there were gaffes such as the interpreter telling PW they were about to be ‘castrated’ when what he meant to say was ‘vaccinated’. One would expect it from absurdity such as a pig being placed on half-rations because it refused to keep its snout clean prior to a dignitary’s visit. One would expect it from occasions when small victories over captors were won: times when there was pride before a fall, times when thefts or deceits succeeded; satisfaction at the skilful repositioning of quota pegs during the course of a day’s digging; times when medicos or leaders won the battle of wills with guards or dodged blows like prize-fighters. It is a greater surprise to see humour shared between oppressor and victim or moments of self-deprecation from an implacable foe. But they happened.

More puzzling still was the humour found at times such as the 1942 sinking of the Vyner Brooke when a high-pitched voice yelled, “Everybody stand still! My husband has dropped his glasses”—and everyone did. It is strange that one of the most popular catch-phrases in Changi was “You’ll never get off the island”, which was still sure to draw laughter from former POWs 40 years on. It is remarkable also that a patient could laugh at an operation performed on himself in primitive conditions with the minimum of anaesthetic; as was the ability to laugh at the predicament of a friend undergoing surgery and give a Bronx cheer to the surgeon—the redoubtable ‘Weary’ Dunlop—as he stitched the patient up and told him he’d be fine. But it is admirable all the same. It is odd to learn that at morning roll-call mates laughed at a stuttering comrade stuck on the Japanese words for seventy-seven while the guard worked himself into a violent frenzy or that the victims of a violent bashing which broke bones and left iridescent bruises on all their fleshy parts laughed heartily when a riverside onlooker at their subsequent bath called them all “Blue-arsed monkeys!” Such strange enjoyment was seen when everyone, even the man himself, laughed at a cobber who at his lowest ebb fell into the unspeakable filth of the latrines or when a dysentery sufferer wearing only a G-string sprayed shit on his mates while doubled over digging a grave. It was the same strong but strange force which induced two men to laugh while guards stubbed cigarettes on their necks for failing to salute. Also extraordinary was the ability not to laugh when prisoners saw a self-important guard fall flat on his face in a massive elephant turd or when an out of control railroad wagon crushed a hated IJA officer’s hand-trolley. Despite their Chaplinesque qualities, neither incident induced so much as the tiniest titter of delight from the ranks of the captives—and that speaks eloquently of their discipline and self-control.

In 1942 LAC Bill Griffiths, RAF, was forced at the point of a dozen Japanese bayonets in Java to move booby-trapped camouflage netting when a terrible explosion blew off both his hands, shattered his face, destroyed both his eyes and fractured his leg so badly he was lucky not to lose it. His recovery from ‘Weary’s’ life-saving operation was long and painful and, in the initial stages, Griffiths begged for his life to be ended, knowing full well that he was so helpless, this was yet another task he could not perform unaided. But he survived and, in the Foreword to Griffiths’ autobiography, ‘Weary’ attributed Billy’s survival to “a mixture of Lancashire pluck and the easy camaraderie in those camps of semi-starvation and death.” It would be hard to find a better example of that “easy camaraderie” than this recollection from the early stages of Bill Griffiths’ recovery:

“Gradually I came to know others in the ward. There were about six other severely disabled chaps; one, an Aussie, had had most of his face blown off and had been terribly burnt, yet managed to be cheerful. ‘I’ve just looked at myself in the mirror,’ he said on one occasion, ‘and my face is a right mess. Reckon my wife’ll throw me out when she sees me. You’re lucky in one way, Billy; at least you can’t see yourself.’ He was the first person to make me laugh, and I can still remember my surprise at finding I could.”

As he put it, “If you can laugh there’s hope.” That remarkable Railway leader, Capt. Reg Newton of the 2/19th Battalion, agreed and cited a case from his later trip to Japan where moneys which had been carefully husbanded and accrued ended up being used for the purchase in Formosa of 100 dozen bottles of tomato purée. This was a classic case of a good plan gone wrong and where the only sensible response was to laugh at the outcome. Improbable shared laughter like this draws individuals and groups together. When the amusement of a mate makes the other bloke laugh along, we see the extraordinary strength that comes from mirth against the odds, that comes from seeing the funny side of an otherwise dreadful situation. Situations such as these reinforce one’s ultimate humanity and hold out hope for happier times. These are the moments when the soul of man sheds its earthly shackles and soars heavenward, when each chortle of a laugh is like the beating of a bird’s wings, allowing the spirit to ascend sufficiently high that the mind’s eye can look on the scene below with astral detachment. When laughter frees a man’s spirit from its physical confines, he is filled with an extraordinary power, the power to distance himself from his suffering and his pain. It may be only fleeting but such moments are vital as they allow him to straighten his battered frame and look the world in the eye with the glint of a god, a god who can watch with amusement the travails of man, even when those travails are his own. They allow the mind’s eye to see past the present to the future beyond, to the peace and the promise of better times ahead; they allow him to glimpse again the basic goodness that beats within the human breast. When a man senses that, he also feels the flicker of the fire being stoked back to life and he knows at his core that with care and a little fuel the blaze will burn anew.

Chris Murphy

June 2021

REFERENCES

AWM. S02922. Interview of Capt. Reginald William James Newton by Tim Bowden. Part Two.

Patsy Adam-Smith. ‘Prisoners of War: From Gallipoli to Korea.’ (1996.) p.400.

Russell Braddon. ‘The Naked Island.’ (1953.) p.284.

Sir Edward Dunlop’s Foreword to Bill Griffiths and Hugh Popham. ‘Blind to Misfortune: A Story of Great Courage in the Face of Adversity.’ (1989.) p.xii.

Colin E. Finkemeyer. ‘It Happened to Us: Mark II.’ (2015.) pp.95-100, 103 115-6, 134-6 & 141.

Betty Jeffrey. ‘White Coolies’. (1954. Reprinted 1976) p.6.

Ray Parkin. ‘Into the Smother.’ (2003.) pp.598-9.

Ian Denys Peek. ‘One Fourteenth of an Elephant.’ (2003.) p.116.

Julie Summers. ‘The Colonel of Tamarkan: Philip Toosey and the Bridge on the River Kwai.’ (2005.) pp.187-8.

Rohan D. Rivett. ‘Behind Bamboo: Hell on the Burma Railway.’ (2005.) p.314.

Reg Twigg. ‘Survivor on the River Kwai: The Incredible Story of Life on the Burma Railway.’ (2014.) pp.216-7.

Stanley Wort. ‘Prisoner of the Rising Sun.’ (2009.) p.84.

Pattie Wright. ‘The Men of the Line: Stories of the Thai-Burma Railway Survivors.’ (2008.) p.180.