NOTES FOR TRIAL LIST

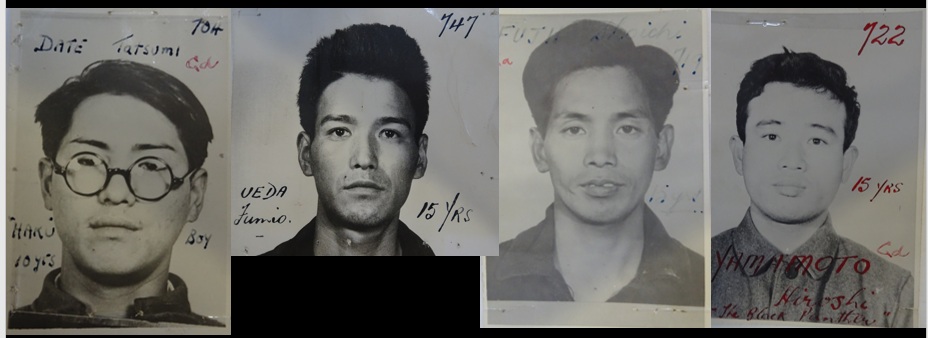

Four Ohama camp #9-B guards responsible for the death from beating and exposure

of Pte Doug Craig, 2/19th Bn, in November 1944.

They are, from the left, DATE Tatsumi, aka ‘the Hako Boy’; UEDA Fumio, FUJII Shoichi and YAMAMOTO Hiroshi. Their sentences are visible on the photos with the exception of Fujii who, like two of the others, was given 15-years’ imprisonment but would have served no more than eleven.

INTRODUCTORY COMMENTS

Before explaining the sources used to construct this list and offering some tips on its extent and reliability, I would like to say that putting faces to names has been an important motivation behind its compilation. For instance, the four guards pictured above were the ones charged with the murder of Pte Doug Craig in Ohama #9-B in November 1944. While the Ohama guards were tried by US authorities and do not feature on Australian trials list, copies of their photos are still held by the NAA in North Melbourne from the days when they were used as tools in the identification of war crime suspects. As discussed elsewhere on this site, precise identification of Japanese personnel by former POWs posed challenges for a number of reasons. First, POWs frequently knew guards (and other members of the IJA) only by their nicknames; a single Japanese guard could also have multiple nicknames since different groups rotated through different camps and guards were also prone to be moved from camp to camp, particularly on the railway. Second, if a Japanese name was known to POWs, it was often a corrupted or mis-heard version for which many variations in Anglicised spellings may have existed. These factors were in addition to the usual problems with faulty recollection and mis-identification. The result is that, for a crime to proceed to the point of prosecution, a great many factors needed to align: the suspect needed to be in Allied custody; the crime needed to have been witnessed by more than one person; someone who witnessed the crime needed to have a memory sufficiently accurate to identify the time, place and other details precisely (qualities which are far less common than most of us presume). That witness’s testimony also needed not to be sharply contradicted by the testimony of others, even if those others were wrong. And, finally, the witnesses needed to be alive at the end of the war. A case in point is that of the notorious Capt. HOSHIJIMA Susumu whose photograph and trial summary are on this list. At his trial at Labuan in January 1946, he claimed that a wonderful spirit of harmony existed between the guards and the 750 British POWs at Sandakan; there was never any physical abuse or punishment because the outstanding co-operation of the British rendered such measures unnecessary. Of course, not one of those 750 British prisoners survived the Death Marches and other measures to contradict that improbable story. By contrast, the Japanese shock must have been palpable when, in the weeks after the end of the Pacific War, they saw the six Australian survivors of the Death Marches and the killings in Sandakan and Ranau. Incidents such as this lead one to suspect that a great many unspeakable crimes perpetrated in the name of the Greater East Asian Co-Prosperity Sphere must have gone unpunished. Nevertheless, photographs of suspects proved a useful tool in the process of identifying and pursuing those liable to prosecution and I believe they remain a valuable tool now for those of us reading and researching this material.

COMMENTS ON THE LIST

From 30 November 1945 to 9 April 1951 Australian authorities conducted 296 trials involving 924 individual prosecutions, (remembering, of course, that the number of individuals will be a lesser figure since some individuals were prosecuted up to four times). These trials were very well-documented and we are fortunate that most of that information has now been digitised. A few years ago, Phillipps University in Marburg put summary documents from all Australian war crimes trials conducted in the wake of the Pacific War up on their website. Early in 2024, access to that material was terminated and the list on the previous page is my attempt to reconstruct that valuable resource. Unfortunately, I do not have the willing volunteers or considerable resources on which universities can call so I do not say that there will not be errors or shortcomings with the list here provided.

As this website indicates, my area of interest is the wartime career of Capt. Reg Newton but trying to make sense of the many confusing references to guards encountered in that material led me to start constructing a list in which I sought to attach proper names to nicknames … and believe me, that proved significantly more challenging than anticipated. The result is that my database now has over 10,000 entries which include photos of Japanese personnel in Allied custody who were of interest to war crimes investigators, those sentenced to various punishments and PDF summary files (of from one to three pages in length) of all trials conducted by Australian authorities. Of course, not many of these trials involved the Burma-Thailand railway or other places where Reg Newton was located while a POW. Australian authorities did try some Japanese railway personnel accused of ill-treatment or murder of Australian POWs, e.g., those responsible for the execution of Australians who escaped from Mergui and Victoria Point in Burma in the middle of 1942. In June 1950 on Manus Island, they tried those believed responsible for the massacre of 110 Australians and 35 Indian troops at Parit Sulong on the night of 22/23 January 1942. One of the most important areas of concern to Australian authorities was to find and punish those responsible for the deaths of almost 2,000 Australian POWs (and another 750 Brits) at Sandakan and Ranau on Borneo. Other trials were conducted based on Australian administrative responsibility for areas such as Papua-New Guinea and Bougainville.

Despite the lack of cross-over between these lists and my research, I have found reading through these documents summarising trials disturbing, fascinating but also very helpful as a research tool, particularly when they turn up the odd bit of gold which clarifies the identity and details of a notorious guard, particularly on the railway. In the hope that others may find the same, I am attempting here to reconstruct that very good list compiled earlier by Phillipps University. (By the way, my several attempts to make contact with them and find out why access to their previous site was shut down have met with a brick wall of silence. No doubt there is a very good reason for that. Hopefully I am not going to find out shortly what that was and regret the decision I have made to make this material available to other researchers and interested parties. Time will tell.)

In compiling this list, I relied chiefly on three sources. The first was the ICC Legal Tools website. This site had a 581-page PDF available at http://www.legal-tools.org/doc/d8f141/ and listed under “South East Asian” cases. Unfortunately, that document covered 703 of Australia’s 924 individual prosecutions. For the remainder, I relied on the excellent name search resource provided by National Archives of Australia website. Rightly or wrongly, I have also sought in the list presented here to combine information from a wonderful summary compiled by or under the leadership of Narrelle Morris of Curtin University, Western Australia. (That document can be downloaded from the NAA.) This is where the information I have provided may get a little confusing because I have sought manually to match records up. This process can be complicated by the different spelling of Anglicised versions of Japanese names which was a problem in the 1940s and remains so now. I do not say with any confidence that the spellings shown here are definitive; sometimes where variations of the same names are given, (e.g., Saito may also be spelt Sato) that is useful as a means of separating individuals with the same or very similar names. In the case of ITO Takeo and ITO Takio, one was a lieutenant-general and the other a captain; I expect the names should logically be spelt the same way but the difference allows for separation. Keeping those comments in mind, I must point out that the original Morris list has the authority of showing the correct kanji characters for those names which will be more precise and allow for finer distinctions than the Anglicised spellings do.

I have also attached to these records photographs (where available) of the individuals concerned. To the best of my knowledge, these photographs have not previously been available online. They can be viewed in person at the National Archives, Australia, office in North Melbourne where the staff have been very helpful to me. There will be gaps at least partly because I found that a significant number of their records for individuals (maybe ten percent at a rough guess) had cards in their files but no photograph. There appears to be a significant number of others that do not have photos but that seems out of my control. (How much of that is due to name spellings or other issues is yet to be determined.) Sometimes the name I have shown for the suspect will not match the name of on photograph but, mostly, I am confident they refer to the same individual. Sometimes, I put the wrong name on the photograph when saving it and, because of knock-on effects, it is too hard to go back and correct that error. Other gaps that exist are for reasons I cannot now explain. Notwithstanding, the photographs have been an invaluable resource in terms of making determinations that individuals whose names and details appeared similar, were, in fact, not the same and sometimes the reverse: individuals whose name may have been spelt differently were, in fact, references to the same person. Moreover, those scanning this material may find, as I did, the intriguing allure of putting a face to a name. Sometimes those who look like butter wouldn’t melt in their mouths, perpetrated the most heinous crimes in those days when they held the whip-hand. What that says about human nature is a larger question which I will leave for discussion at another time.

Finally, in constructing and expanding this website, I am feeling my way down a dark corridor. The publication of this list represents a significant personal step forward in terms of storing and making retrievable online a considerable amount of information. Like everything here, this list should be considered a “working document” since, in its current form, it is almost certainly imperfect. While saying that, I can assert with even greater assurance that it will never achieve “perfection” but I can say it will almost certainly be improved over time. I should add that I make it available in the tradition of those volunteers who have gone before and done tremendous work in compiling and freely sharing information, e.g., the Ballarat POW Memorial site, the FEPOW site (with Ronnie Taylor prominent there), the Roger Mansell site, the Peter Winstanley site and the 2/4th MG Bn Association site to name just a few. In that spirit, I make this material available and hope it helps you, as I have been helped by great-hearted others, in my journey seeking to understand the details, the complexities, the intricacies, the nuances and the tragedy that was the Pacific POW experience.

Chris Murphy

March 2025

SOME HOUSEKEEPING

- At present my skills do not allow the PDF summary to open in a new window so users should employ the back arrow to return to the list page from PDFs. (This seems also to sometimes be required from photos.)

- Sometimes the name by which I have listed this individual will not be the same as the name given for the photograph but, rest assured, I have looked at these connections fairly closely and, while I’m not pretending my work is foolproof, I am saying there will or should be a good reason why I connected these records. However, if it is felt that further investigation is warranted or more detailed justification required, contact me and we can discuss it. I guess the point I am trying to make is that the master list from which I was working contains a great deal more information than I was able to put up here online.

- The location information provided shows where the trial was conducted and also where the individual was stationed, particularly when any alleged misconduct occurred.

- There are references to the Legal Tools document which may seem repetitive and they mention page numbers which are not shown here. Including those page numbers would have made the list here all too busy in my opinion so I have left them out. Taking out the references to the Legal Tools document would have been a task greater than my brain or my patience could sustain.